Guests can appreciate the unique natural behaviors of ducks in many habitats at the Zoo and Safari Park.

BY Eston Ellis

Photography by Tammy Spratt

The old saying that on a rainy spring day “it’s fine weather…for ducks” is actually true. As another old adage puts it, water just “rolls off a duck’s back,” because they are well adapted for living in the water, near the water, and in the rain. But rainy or sunny, any spring day is ideal for getting to know the full-time resident duck species that live, swim, eat, and nest in the many habitats of the Zoo and Safari Park.

IN FINE FEATHER

In many duck species, including bufflehead (at top) and wood ducks (above), males have more brightly colored plumage than females during mating season. This example of sexual dimorphism helps males attract an interested female.

What Makes a Duck a Duck?

Ducks—along with geese and swans—are members of the Order Anseriformes. They share many similarities, and most people can quickly identify a duck, a goose, or a swan on sight, explained Dave Rimlinger, wildlife expert at the San Diego Zoo. “In certain orders, it’s hard to tell where some birds belong and how they are related. But others, like penguins or ducks, you can tell just by looking.”

THINK PINK

Both male and female black-bellied whistling ducks have the same distinctive pink-to-orange bills and feet—an example of a species that does not exhibit sexual dimorphism.

While there are more than 100 duck species worldwide, most share a few easily recognizable characteristics, including bills, webbed feet, and the ability to remain buoyant on the water’s surface. Ducks swim at an average speed of two to three miles per hour, but they can easily put on a burst of speed when necessary, propelled by powerful leg muscles, with webbed feet fully spread for maximum thrust. Further helping ducks stay afloat are internal air sacs that extend from their lungs into their body cavity, and a layer of down below their external feathers that traps air for buoyancy and provides insulation against temperature extremes.

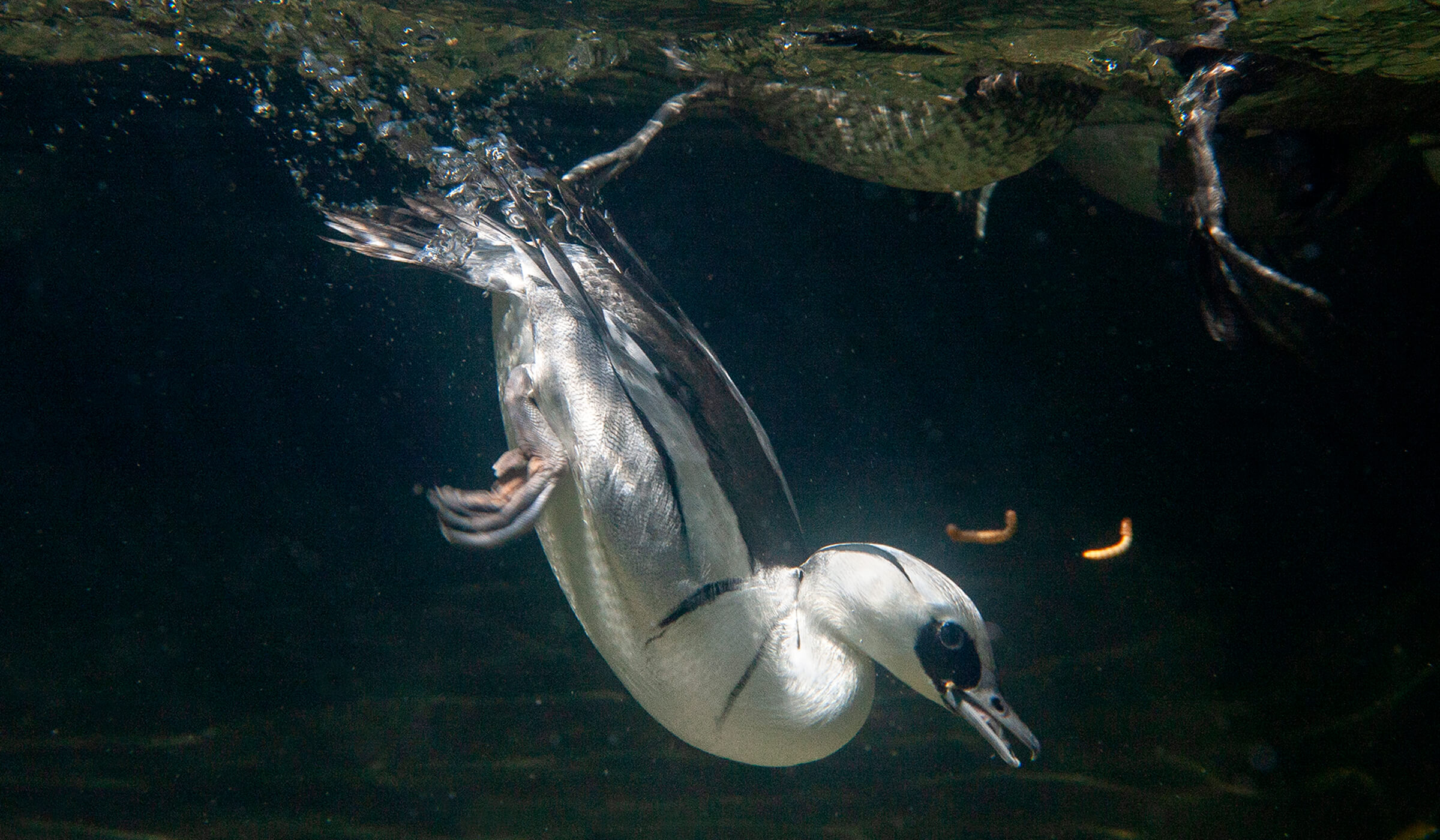

DIVING IN

While dabbling ducks feed at the water’s surface, filtering their food out of a bill full of water, diving ducks dive underwater to go after fish, vegetation, and other tasty treats.

Do They Dabble or Dive?

There are two main categories of ducks: dabbling ducks and diving ducks. Dabbling ducks are filter feeders, which find their meals near the water’s surface. They dabble their bills in water to catch plankton, crustaceans, and other small food items, trapping them as the water runs out of their bill. Diving ducks, as their name suggests, dive underwater to go after plant material or fish below the surface.

DESIGN FOR DABBLING

Dabbling ducks, like the harlequin duck mother and duckling at left and the male at right, have oval-shaped bodies with feet positioned in the center, to help them float on the water’s surface and move easily across a waterway. On land, that shape and leg position makes them walk with a waddle.

Dabbling ducks have elongated, oval-shaped bodies, with feet positioned at the center to help them float gracefully across a pond, and take off in flight from the water without requiring a running start. However, that body shape makes them look much less graceful on land, and gives them their characteristic waddle.

DUCKS BEING DUCKS

Behaviors guests might see when watching ducks at the Zoo or the Safari Park include preening feathers (like the red-crested pochard at left is doing), and catching fish, like the scaly sided merganser at right.

Diving ducks have a more compact body, with legs positioned closer to their rear end and the tail closer to the water’s surface. When this type of duck dives, it closes its wings tightly to squeeze out air between its feathers and decrease its buoyancy. Diving ducks use their feet to maintain a hovering position in the water or to push forward when diving. They typically stay under for 10 to 30 seconds, but some may stay submerged for a minute or more to grab an underwater snack.

Travel Time

One thing nearly all ducks in wild habitats have in common is that they are migratory animals. Twice a year, ducks embark on long flights, sometimes thousands of miles from their northern breeding grounds to their southern wintering grounds and back again. Many ducks fly at speeds of 40 to 60 miles per hour, at heights ranging from just above the ground to 20,000 feet in the air. Simultaneous molting helps get each duck in a species prepared at the same time, allowing them to migrate in large groups for safety.

WINGING IT

Diving ducks, like the ring-necked duck (left), have flatter, swept-back wings for high-speed flight over open water. Dabbling ducks, like the perching Mandarin duck (right), typically have large wings that allow for a quick takeoff from the water, but slower flight speed.

Males molt just before the breeding season, and emerge with plumage in bright colors to attract a mate. Most will pair bond for a season, but after the female lays her eggs, males do not stay around to raise chicks. Ducks are social and like company. “Most ducks not only hang out in groups of their own species, but associate with other species as well,” Dave said. “Ducks on a river are the exception, where one pair may ‘own’ and protect one section of the river.”

G’DAY, DUCKS!

At the Safari Park’s Walkabout Australia, radjah shelducks are often seen in shallow water—but when they’re on shore, they are surprisingly fast runners.

What to Look For at the Zoo and Safari Park

For guests at the Zoo and the Safari Park, spring is an especially good time for duck watching. “They are already starting to pair up,” said Andrew Stehly, wildlife expert at the Safari Park. “It’s really interesting watching their courtship displays,” Dave added. “While some species of birds are very secretive, ducks are not: they don’t care who’s watching. Males have a whole variety of postures, throwing their heads back, puffing themselves up. You’ll hear some vocalizations, but mostly you’ll see postures that are only displayed at certain times of courtship.” Year-round you’ll see ducks preening—aligning and oiling their feathers.

DISTINCTIVE BILL

Males of some duck species, like this ruddy duck, show off a brightly colored bill during mating season—another example of sexual dimorphism.

“There have been ducks at the Zoo ever since there has been water here,” Dave said. The first ducks arrived in the 1920s, and there have been wood ducks since 1932, and Mandarin ducks since 1938. Today, guests have a rare opportunity to see more than 30 species at the Zoo: at the Flamingo Lagoon, the Lower Duck Pond on Park Way, the Owens Aviary Rain Forest, Scripps Aviary, the Marsh Aviary on Tiger Trail, and the Northern Frontier Polar Aviary, where underwater viewing allows guests to experience the grace and antics of diving ducks. At the Safari Park, guests can also see more than 30 species of ducks: at the Wings of the World aviary, Hidden Jungle, the Chilean Flamingo Pond at Safari Base Camp, Mombasa Lagoon, and Walkabout Australia.

CRITICALLY ENDANGERED

Fewer than 700 Laysan ducks still exist in their native habitat in the Hawaiian Islands. The San Diego Zoo and Safari Park have both been involved in breeding programs to increase the population of this species, and guests at the Safari Park can see Laysan ducks in Wings of the World.

Duck(s) and Cover

In their native habitats, duck species currently face many threats, including habitat destruction for development and agriculture, climate change affecting key waterways, contamination of waterways, and overhunting. “Ducks rely so heavily on water,” Dave said. “Right now, many face challenges due to pollution of water that attracts waterfowl. While things may be okay where they are breeding, there might be serious habitat destruction in areas where they migrate. Suitable areas for waterfowl are, unfortunately, disappearing.”

HEAD TURNER

During breeding season, the male hooded merganser expands its fan-shaped, collapsible crest to make its head look even larger—and makes deep, growl-like calls to attract females.

Be a Friend to Ducks

While ducks face serious habitat challenges, there are a few simple things people can do to help ducks survive in their own communities. One is to avoid throwing coins in any waters where ducks might find them, swallow them, and be killed. “Many of the diving ducks go after small fish and things that are shiny,” Dave said. “When a coin is in the water, it attracts their attention. At the Zoo, we’ve lost some pretty rare ducks to coin ingestion—and some species are so prone to coin ingestion that we don’t keep them anymore.”

SPOTTING SPOTTEDS

Safari Park guests can see (and hear) spotted whistling ducks in Walkabout Australia. Other whistling duck species at the Park include northern black-bellied whistling ducks in Wings of the World and white-faced whistling ducks in the main lagoon.

Another way to help local ducks is to avoid something people think is fine: feeding them bread. Why? It has relatively low nutritive value and is actually bad for waterfowl—birds that eat a lot of it can develop some severe malformations in their wings and bones. And if bread is left in the water until mold forms, it can prove toxic. A better alternative is to feed ducks romaine lettuce, which more closely matches their natural diet.

REAL TEAL

Native to Asia, the baikal teal is often found in large groups. Guests can see this colorful dabbling duck in the Zoo’s Lost Forest and the Park’s Wings of the World.

If you see a duckling that appears to be lost or on its own, do not pick it up. The mother is probably nearby, although out of your view. If you have concerns about waterfowl you see at the Zoo or the Safari Park, contact a volunteer or staff member and let them know.

Ducks are colorful and gregarious, and spring is a great time to discover their unique behaviors. Whether it’s raining outside, or the sun is shining bright, ducks remain active, and they are continually fascinating to watch.