The Side Track

The San Diego Zoo has some turtle species with a twist: a long, flexible neck that they bend sideways, giving them the name side-necked turtles.

BY Wendy Perkins

Photography by Ken Bohn

There are more than 350 species of turtles and tortoises that share our planet. They are categorized into two groups, based on how their neck retracts. Most pull their neck straight in, but others throw a curve by folding their neck to the side instead.

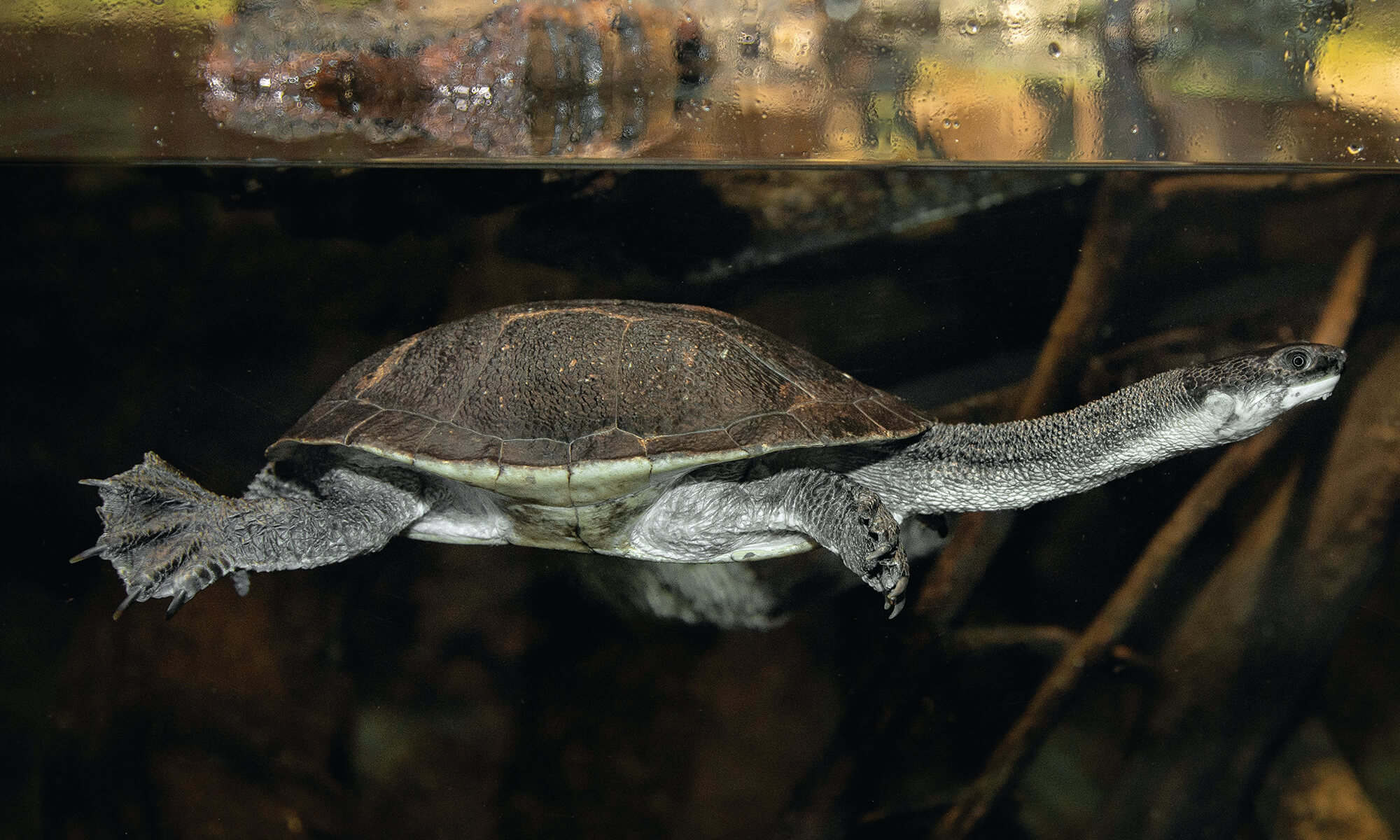

UNDERWATER, DOWN UNDER

The broad-shelled snake-necked turtle Chelodina expansa, travels waterways with its neck fully extended. This genus has only four claws on its forelimbs, while other turtles in its native Australia have five.

Those that pull the neck straight in belong to the Suborder Cryptodira: tortoises, sea turtles, and box turtles (cryptodires). Those in the Suborder Pleurodira, however, have a different angle. Rather than pulling into the shell, a pleurodire bends its neck sideways, tucking its head along its side. Although the neck and head are not hidden, a generous overhang of the carapace (top shell) offers protection.

Watching some of the pleurodire species in Reptile Walk’s Turtle Building reveals another amazing attribute. If a flexible, folded neck doesn’t catch your eye, the extension of it will. These turtles have surprisingly long necks—earning them their other common name of snake-necked turtles.

IS THAT A SMILE I SEE?

A rounded jaw and short snout create what looks to be a smile on the red-bellied short necked turtle Emydura subglobosa of Papua New Guinea and northern Australia.

Neck and Neck

The name Pleurodira translates from Latin as “side neck,” and the common names for this group vacillate between side-necked and snake-necked. Cryptodira means “hidden neck” and is just as apt. What makes one neck different from the other? Why don’t side-necked turtles simply pull their head in, the way cryptodires do? The neck function is based on form.

All turtles alive today have eight cervical vertebrae, but a difference in structure contributes to each group’s retraction style. Unlike cryptodires, the neck bones of pleurodires are narrow in cross-section, and one or more of these bones is convex (curving outward) on both upper and lower surfaces. This allows them to function as a double joint, resulting in the side-necked turtle’s impressive neck flexibility.

MASTER OF CAMOUFLAGE

The matamata turtle Chelus fimbriatus lives a well-camouflaged life in the Amazon basin in Guianas, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, and Bolivia.

Big Gulp

Without a doubt, one of the side-necked turtles, the matamata Chelus fimbriatus, is the strangest-looking turtle in the world. Its appearance and name even sound like something Dr. Seuss might have created. It is rarely confused with any other species, because there is nothing that even comes close.

With a jagged-edged, reddish carapace, lappets hanging from the neck, and a habit of staying still, the matamata looks like the dead leaves and mud it rests among at the bottom of shallow, stagnant bodies of water. It’s a perfect camouflage for this ambush predator! As small fish, frogs, tadpoles, and other potential prey approach, the turtle makes its move. Swinging its head in the direction of prey, it suddenly opens its mouth wide, creating a strong suction that pulls its meal into its gaping maw.

CALM WATERS

Red-headed river turtle Podocnemis erythrocephala tend to live in quiet water zones like swamps in Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela.

The matamata may be unique in appearance, but it isn’t the only side-necked turtle to just “let it flow” while feeding. Red-headed river turtles Podocnemis erythrocephala are mostly herbivores. Feeding on aquatic plants requires some biting and tearing, but these turtles also use the open-mouth technique to take in fine particles of algae and bits of decaying plants floating at the surface of the water.

SOAKING UP THE SUN

East African black mud turtles Pelusios subniger subniger spend time basking on logs and rocks in their southeastern Africa, Seychelles, and eastern Madagascar habitats.

The Water Is Fine

The sinuous throat of pleurodires is a trait that sticks out like a…well, a neck. But another unique trait is concealed beneath the shell—and it brings up the rear. The pelvis of a pleurodire is fused to the carapace and not flexible. In contrast, cryptodires have an unfused, more flexible pelvis. “Studies of turtle and tortoise movement suggest that flexibility is beneficial to moving on land,” explains Brett Baldwin, a wildlife care expert in the Herpetology department. “But a fused pelvic region may be beneficial to moving in water. A pelvis fused to the carapace is actually an ancient trait, and pleurodires are one of the most ancient turtle groups living today.”

Without needing space for a flexible pelvis, the carapace of side-necked turtles has a lower, more streamlined profile. They don’t leave the water often, spending most of their time resting at the bottom of wetlands, streams, rivers, and lakes. With a few exceptions, most feed on bottom-dwelling mollusks and worms, tadpoles, insects, crabs, and small fish. The East African serrated mud turtle Pelusios sinuatus even has a helpful habit: it feeds on ticks attached to large mammals that wade into waterholes.

BIG TURTLE

Male Madagascar big-headed turtles Erymnochelys madagascariensis can reach more than 18 inches in length and weigh around 20 pounds.

While some side-necked turtle species haul out on beaches to bask in the sun, others like to stay closer to water and use logs as a safe spot to warm up. But when it’s time to lay eggs, a female cautiously sets out to find a nesting spot on land—sometimes traveling thousands of yards from the safety of the water. After laying and covering her eggs, the female returns to her aquatic home. The incubation time for many species varies greatly, depending on when the rains arrive.

MULTI-USE ADAPTATION

The long, serpentine neck on pleurodires like this Roti Island snake-necked turtle gives greater range when snatching prey and allows the animal to snorkel for a breath while keeping most of its body well beneath the surface.

The inches in length a female’s South American river turtles Podocnemis sp. carapace can reach. This is the largest of all the side-necked turtles.

The inches in length a female’s South American river turtles Podocnemis sp. carapace can reach. This is the largest of all the side-necked turtles.

A Rare Sight

Their propensity for staying in the water makes side-necked turtles a challenge to see in their native habitats. In some cases, plummeting populations, severe droughts, and land-use changes ratchet up the rareness. For example, Roti Island snake-necked turtles Chelodina mccordi are critically endangered. They are threatened by ecosystem modifications for human industries and the resulting waterway pollution; invasive introduced species and diseases; and drought. These factors combine to create an alarming situation on their island home in Indonesia, and their populations are severely diminished.

Then in the early 1990s, a spike in the number of Roti Island snake-necked turtles taken for the international pet trade devastated the population. Within a few years, the island population was considered ecologically extinct. Breeding and building assurance populations under protected care—such as zoos and aquariums—is working to bring these turtles back.

Building assurance populations, community conservation efforts, and setting aside protected areas are vital parts of the effort to bring side-necked turtle species—and other endangered turtles and tortoises—back from the brink of extinction. These species have been on Earth for a very long time. Here’s hoping that together we can make sure their ancient lineage continues.