BY Wendy Perkins

Photography by Tammy Spratt

Sporting eye-catching crowns of arching fronds and a quiet yet stately bearing, palm trees seem to have a regal air. In addition to the relaxing effect swaying palms have on our busy minds, these majestic plants have long been important and useful for humans as a resource and symbol. Indeed, the famous 18th-century naturalist Carl Linnaeus was so impressed by this group that he ordained them Principes plantarum, “prince of plants.” The Zoo and the Safari Park are proud to host many spectacular species of these noble plants.

BLOOMING BOUNTIFUL

A multitude of tiny palm blossoms hold forth on a flowering stalk called an inflorescence. Pollen from the male flowers is transported to the female blooms by pollinators, such as bees, as well as the wind.

The common names of some species reflect this royal connection, and the dignitaries of the plant realm are represented worldwide. Crowning the monarchy is the king palm Archontophoenix cunninghamiana of Australia, and naturally there is a queen palm Syagrus romanzoffiana, but she hails from South America. The princess palm, Dictyosperma albumis is found only on the Mascarene Islands east of Madagascar. Ironically, although it is almost extinct in the wild, it is a popular landscape plant that has been successfully propagated commercially.

The palm family Arecaceae is an old and large one, populated with about 210 genera and 2,700 species. Growth patterns range from shrubs to trees and even vines. Found on every continent except Antarctica, palms are most common in the tropics and subtropics. While most species prefer hot, wet habitats, some have put down roots in dry niches like deserts and 13,000-foot-high mountaintops.

The Palm Principle

For the most part, palms are tender plants. They have a single growing tip, called the apical meristem, that is essential to the survival of the palm. If the meristem is damaged, the plant dies. However, fibers and leaf bases surrounding the growing tip provide enough protection in some cases to help a few species grow where it might seem too cold—such as the windmill palm of China, which survives some snowfall each year.

ALWAYS REACHING

Most palms don’t produce lateral branches from the trunk. Instead, all growth arises from a single apical meristem, or growing tip, at the top of the plant. Palms are always moving up in the world.

While they are seed-bearing, flowering plants, palms do not have bark or woody tissue. Rather, the trunk consists of bundles of dead fibers that at one time were connected to leaves. In the center of the trunk, active fibers feed the new growth at the top of the plant. Most palms also don’t have a branching habit as do most trees, growing only from the top. However, some species send up more than one trunk from axillary buds, which form new shoots resulting in a clustering formation.

FRONDLY

The structure of a palm’s fronds earn it a place in one of two categories: the leaflets of a feather palm (left) are divided, giving it the feathery appearance it is named for. A fan palm’s leaflets are joined, creating a solid surface like a…well, you get the picture.

Palms bear big and often bold structured leaves, called fronds. Frond type is one characteristic used to identify a species. Broad palmate leaves grow like hands in a bunch at the end of a stem. Pinnate leaves are more feather-like in structure, with blades extending all along either side of the stem.

On the Hawaiian Islands, the palmate-fronded loulu palm Pritchardia ssp. welcomed the first human inhabitants with shelter and security. As the slow-growing plants stretch for the sky, they shed their large, strong leaves, which were (and still are, in some cases) used for roof-thatch material. But the large leaves also served as portable protection from the rain—the common name of this palm is the Hawaiian word for “umbrella”: loulu. Reaching 25 to 60 feet tall, the extremely hard wood of the trunks was also used to make spears.

EDGY BEAUTY

Bipinnate leaves make the fishtail palm unique among its kind. The slightly ragged edges of the divided leaflets do indeed look like a a fishtail.

Pinnate-fronded palm varieties abound, but perhaps few are as striking as the aptly named fishtail palm Caryota urens, native to India, Burma, and Sri Lanka. Bearing doubly pinnate fronds, it is one of the fastest growing of all palms, reaching maturity in about 20 years. There is a penalty, however, for this rapid rate of growth. The fishtail palm is known botanically as a monocarpic plant—it dies after flowering, while most other palms begin flowering while young and continue to do so. The flowering period of a fishtail palm can span five to seven years. The first infloresence emerges near the top of the plant, and each succeeding year, another flower spike is sent out farther down the trunk.

Princely Bounty

Palms have long been a useful plant for Earth’s life-forms. Quite early in our history, humans realized that the palm had many uses that would make life easier. The trunk provided fuel, building materials, and fiber that our ancestors quickly learned to transform into paper, pound into cloth, and twist into cordage. The fruits provide food, oil, dye, and sugar. Palm sap yields starch, sugar, and when fermented, wine.

FRUIT FOR THE FUTURE

After pollination, a palm flower forms a seeded fruit, called a drupe. Animals unknowingly spread the seeds by eating the drupes and depositing the seeds elsewhere after a trip through their intestinal tract.

When most people think of a food from a palm tree, the coconut tree Cocos nucifera usually springs to mind first. While it may be the most well-known in contemporary Western culture due to movies, cartoons, and the burgeoning health market, most other palms are just as important as a resource to the humans—and animals—around them.

VERTICAL LIVING SPACE

As palm fronds die and droop, they create shelter for birds and small mammals—including rodents. To keep the latter at bay, most homeowners have the dead fronds removed, but away from human habitation, palms create an oasis for wildlife.

The Pondoland palm Jubaeopsis caffra is a clumping palm native to South Africa, where it grows along the banks of rivers. It yields a fruit that looks like a miniature version of the famous coconut. Despite (or perhaps because of) its smaller size, it is eagerly eaten by people and baboons, while weaver birds gather frayed bits of fronds for their nests.

The pindo palm (also called jelly palm) Butia capitata is another princely plant that can make mouths water. The ripe fruit is said to taste like a mixture of pineapple, apricot, and vanilla—but soil conditions can sometimes give rise to more of a banana flavor. Native to Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, this slow-growing palm is often used in landscapes along the west and east coasts of the US.

GETTING A GRIP

Palm roots are described botanically as adventitious, meaning they sprout directly from stem tissue rather than from other roots. In fact, they often sprout from the trunk just slightly above ground, as well as below. Look closely and you’ll notice that all the roots are of a similar thickness.

Even the wax from the surface of palm leaves and trunks has been harvested and put to use. Consider, for example, the carnuba wax palm Copernicia prunifera from the savannas and forests of Brazil. Its characteristically blue-green fronds have a coating of valuable-to-humans, heat-resistant wax. Harvested by scraping the leaves, the wax is used in a variety of products like candy, cosmetics, dental floss, and most popularly, car wax.

The largest genus of palms, Dypsis, contains more than 150 species—all found only on Madagascar. One species, the 20-foot-tall butterfly palm Dypsis lutescens, is a popular houseplant, but is endangered in its native habitat. Another member of the “tribe” is the triangle palm Dyspis decaryi. Found within the island’s rain forest, this palm’s leaf bases are evenly spaced around the trunk, forming a triangle.

FIRST OF ITS NAME

The Bismark palm Bismarkia nobilis is the only member of its genus. In its native plains of Madagascar, the plant can grow to about 40 feet tall. The species is often used in landscapes, where the 9-foot-wide fronds add visual impact.

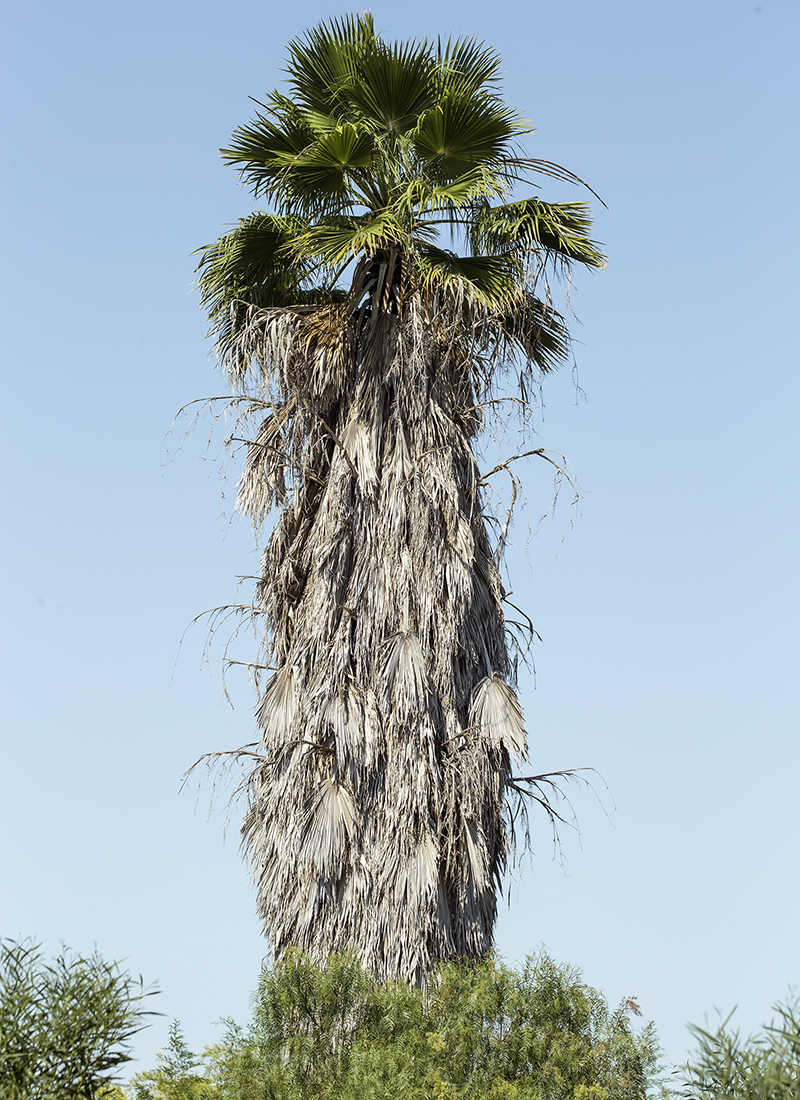

At the Park, guests can get a glimpse of the Mexican blue palm Brahea armata—one of the most widespread endemic palms of northern Baja California, Mexico. Its impressive bluish fronds are three to nearly seven feet wide and three feet long. As they die, the leaves droop but don’t always drop off, creating a shaggy mane formed by the collection of old leaves. It is readily used as housing by rodents, birds, and insects.

A SURPRISING PAIR

At both the Safari Park and the Zoo, keepers provide certain animals with palm fronds as a form of behavioral enrichment. Although they would never encounter these plants in their native range, the polar bears at the Zoo are deeply fond of fronds! The keepers sometimes sprinkle scents on the leaves, and the bears eagerly roll on and wrap themselves in the greenery.

Palms have held court on Earth for millennia, and hopefully will for ages to come. Become a “royal watcher”: take note of the regal sentries in your surroundings, and appreciate their enduring beauty and adaptability.