BY Donna Parham

Photography by Ken Bohn

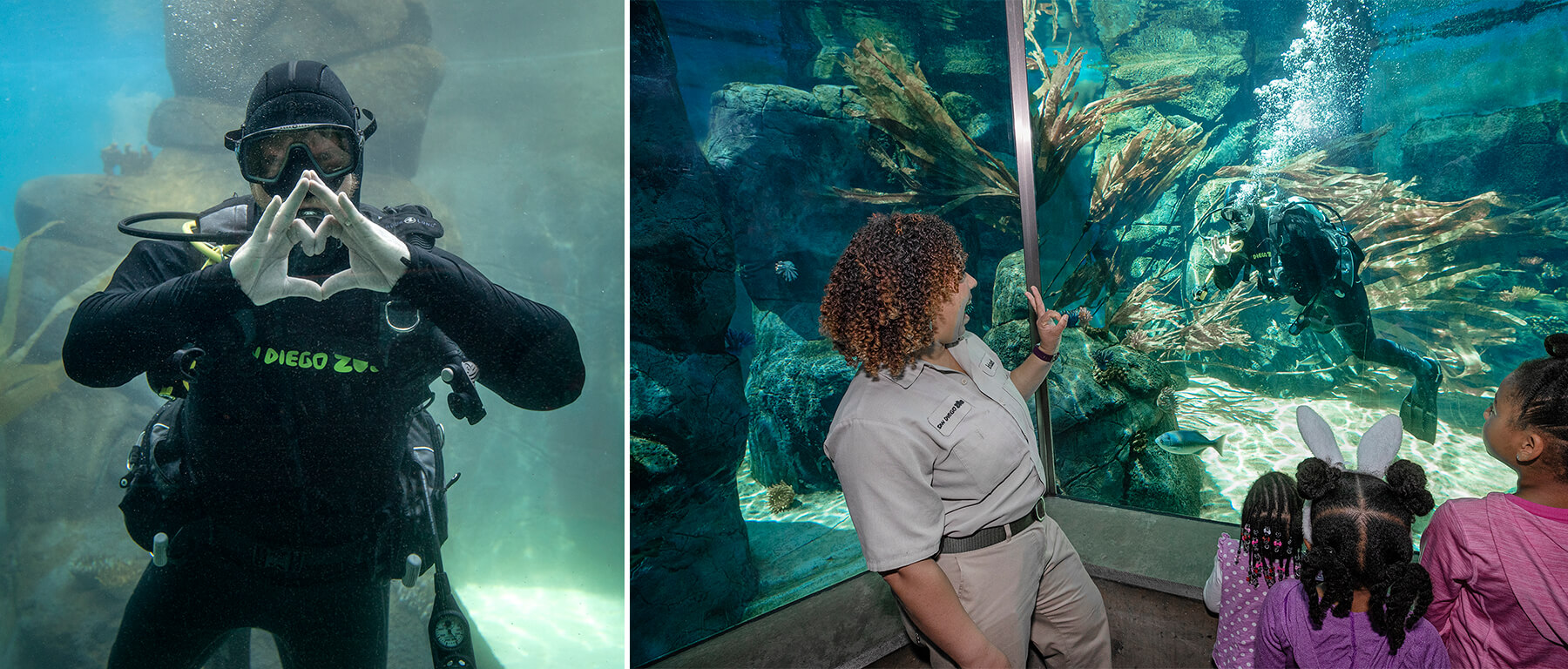

A scuba diver glides through the re-created kelp forest in the penguin pool and waves to the mesmerized observers in the underwater viewing area. Leopard sharks and other fish swirl around her as she feeds the smaller fish with a squeeze bottle. On this side of the glass, an interpretive volunteer explains what the diver is doing and fields a stream of questions. One guest wants to know if the sharks ever eat the penguins and smaller fish. The answer is no. Penguins are too big and too fast; the small fish are fast too, and they have plenty of hiding places amongst the rocks and kelp in the large pool. Besides, none of them are part of the diet of these sharks, which eat squids, clams, capelin, and herring.

HOME, SWEET HOME

In the Zoo’s Ituri Forest, river hippos Hippopotamus amphibius share their home with African cichlids Maylandia and Aulonocara.

UNDERWATER WORLDS

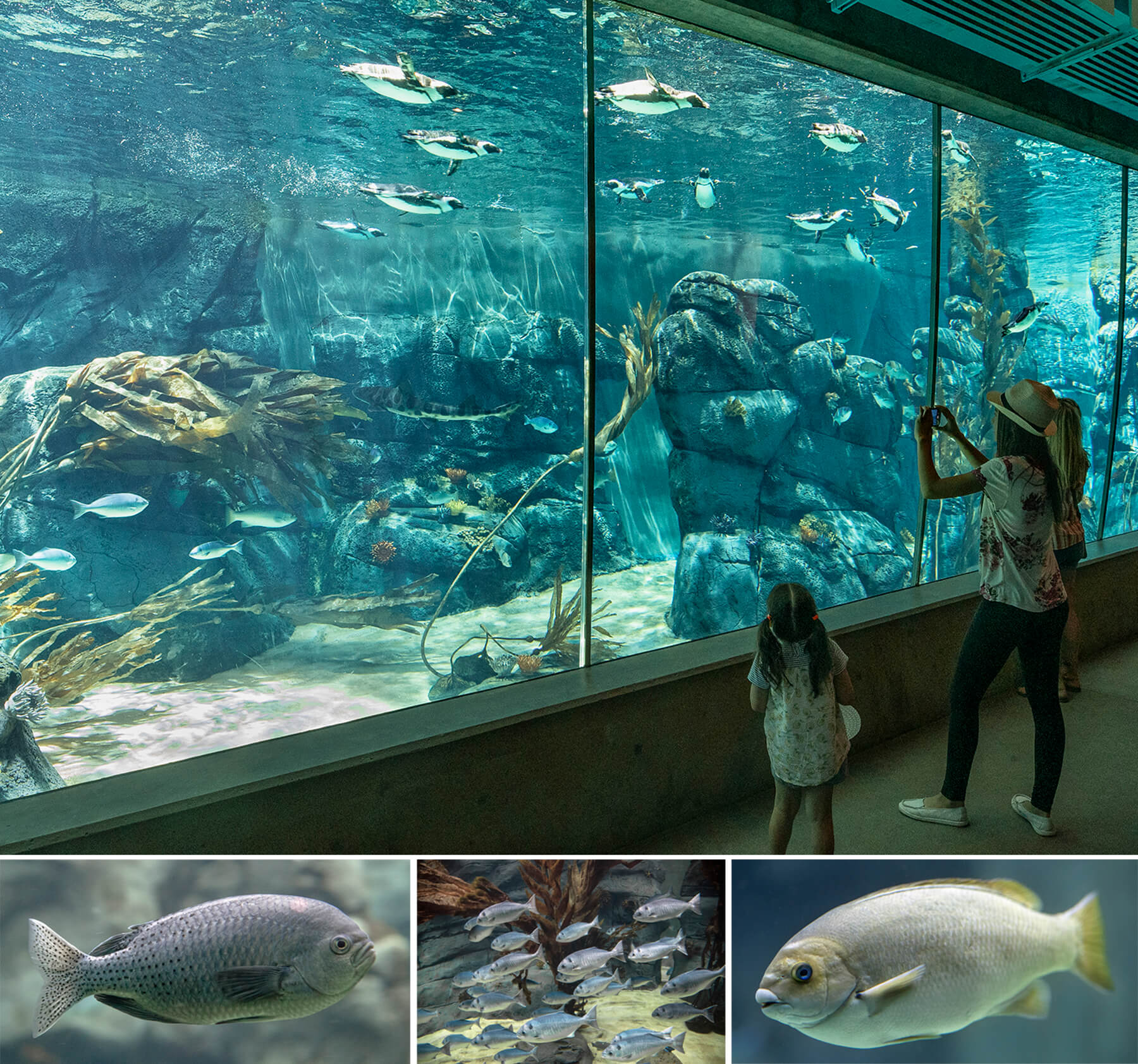

Laura Hilstrom is aquatics lead keeper in the Zoo’s herpetology and ichthyology department. She appreciates the Zoo’s multidimensional exhibits, where fish share habitat with mammals, birds, or reptiles. “It’s a more realistic picture of what’s going on in wild habitats, outside of the Zoo.” she says. “The naturalistic environment of a mixed-taxa habitat is also great enrichment for the animals. There are things moving around, whether it’s a croc, or a penguin, or a hippo, and there’s always some version of interaction and visual interest.” In addition to the sharks and other marine fish in the penguin habitat, visitors can see freshwater fish displayed with birds in Owens Aviary, with birds and lizards in the Africa Rocks aviary, and with turtles and dwarf crocodiles in the Africa Rocks croc habitat. In Monkey Trails, fish share habitat with pygmy hippos, slender-snouted crocodiles, and monkeys; and in Ituri Forest, they can be found in the river hippo pool. Terrace Lagoon is home to several brightly colored koi.

WEST AFRICAN RAIN FOREST

African cichlids Maylandia and Melanochromis auratus provide a glimpse into the world of the West African dwarf crocodile Osteolaemus tetraspis tetraspis.

Laura says that many people are surprised to learn that we have fish at the Zoo. “It’s kind of a teaching moment,” she says. “People learn that there’s more at the Zoo than elephants and giraffes. There are cool fish, too, and we support them just as we do the other animals we have in our care.” Laura, who has more than 20 years of experience caring for fish and other aquatic animals, says that many people have misconceptions about fish. “Some people don’t even consider them animals,” she says. “But they have brains, and personalities, and an ability to feel pain. They are a different type of animal, so keepers need a different perspective when taking care of them.”

PEACEFUL RESPITE

Tucked away from the bustle of Front Street, the Zoo’s Terrace Lagoon offers serenity—and a home for multicolored koi Cyprinus carpio carpio koi.

For one thing, says Zoo veterinarian Ben Nevitt, DVM, “All of the equipment we use with fish needs to be waterproof.” But there are other, less obvious, differences in fish veterinary care. For example, “Anesthesia for fish is completely different than for all the other animals at the Zoo,” he explains. “We keep them in the water and use anesthesia that they can absorb through their gills to perform exams. Our new, beautiful marine management building at Africa Rocks was built with this in mind, providing tanks that can be used for exams, treatments, and procedures.”

THE MORE, THE MERRIER

At Monkey Trails, hundreds of freshwater fish help illustrate the natural habitat of slender-snouted crocodiles Mecistops cataphractus. The crocs don’t eat the small fish, which include black catfish Synodontis nigrita, porthole catfish S. nummifer, and cichlids Maylandia and Tropheus moorii.

UNTROUBLED WATERS

“We’ve had good luck with really healthy fish,” Laura says. But it’s more than luck. On a daily basis, keepers check fish for body condition. “We look at their stomachs to see if they are getting fat or skinny—our goal is to keep them right in the middle or slightly above the midline,” she says. To keep them in that zone, keepers adjust food amounts or food types. Keepers also keep an eye out for scrapes and bumps that might indicate illness or injury, moving fish for treatment when necessary. Laura and Ben also have established protocols for introducing new fish. “Each fish has to be cleared medically before it goes on exhibit,” Laura says. “To make sure they aren’t carrying parasites that would infect other animals, we take ‘skin scrapes’ and tiny ‘gill snips’ and examine them under a microscope.” If necessary, they treat the fish for external parasites—by bathing them in therapeutic chemicals—or internal parasites—by putting medicine in their food.

IT’S A BIRD…IT’S A FISH!

A stroll through Owens Aviary includes a view inside the top-level pond. Residents include banded archerfish Toxotes jaculatrix (at left) and spotted scat Scatophagus argus.

Another important part of the credit for keeping the fish healthy, says Laura, goes to the Zoo’s water quality department, who maintains the life support systems for the animal habitats. With more than 30 years of experience as an aquarist, Thad Dirksen manages the water quality team and maintains the highest-level water quality for our animal collection. “Mixed species pools are much more challenging to manage, due to their complexity,” Thad says. “The most complex system at the Zoo is the penguin and shark habitat,” where the filtration area—with six high-pressure sand filters, three carbon filters, and three protein skimmers—maintains the proper environment for our aquatic animals.

FISH KISSES

In Monkey Trails, freshwater fish get a snack as they “clean up” pygmy hippos Choeropsis liberiensis. Species include the Nyasa golden cichlid Melanochromis auratus and Maylandia cichlids.

The sand filters trap large particles in the water, and the carbon filters absorb organic compounds and help clarify the water. The real heroes, though, are the billions of beneficial bacteria that live on the surfaces of the sand and other parts of the filtration system, and turn ammonia—from fish waste—into safer nitrogen compounds. “Without biological filtration, the fish’s own waste would eventually cause fish stress,” Thad says. An assistant lab technician analyzes the water chemistry on a daily basis, and the results tell Thad if the equipment that maintains water quality is working correctly.

CHORUS LINE

Penguins and sharks tend to steal the show at the penguin habitat in Africa Rocks, but the large saltwater aquarium also displays fish species native to Southern California, including (left to right) blacksmith Chromis punctipinnis, Pacific halfmoon Medialuna californiensis, and opaleye Girella nigricans.

COME ON IN—THE WATER’S FINE

In addition to working closely with Thad’s team and veterinary staff, Laura works with keepers and divers. “The biggest part of my job right now is developing protocols—for fish care, diets, cleaning, handling, treatment, diving, and record keeping,” she says. She likes to spend time observing her aquatic charges, but she admits that “getting eyes on everything” is the most challenging part of her job. “This is a large zoo, and we have fish all over the place.”

Laura says that her favorite part of her job is diving with the fish. “You get to experience their environment, interact with them, and feed them.” She wants people to know that the information we learn by taking care of animals like this in aquarium settings can be used to help understand how animals in the wild are affected by environmental changes like global climate change and habitat destruction. As Laura says, “It’s interesting to connect people to fish and ocean animals, so they can realize that what we do as humans affects the home of aquatic animals.”