BY Karyl Carmignani

Photography by Ken Bohn

Conservation of a large-bodied, charismatic, highly visible mammal should be a straightforward operation. Nearly everyone on the planet can identify them, and they are not venomous, vicious, harmful, or otherwise a threat to humans. Their image adorns home décor, children’s books, games, pajamas, and everything in between. The mighty giraffe symbolizes self-confidence and acceptance…and pretty much all that is decent in the world. Whether gliding across the savanna, galloping away from a lioness, or nibbling at an acacia tree, giraffes move through their world with a great deal of grace. Despite these attributes, giraffes have quietly declined significantly in numbers in the past three decades, largely due to increased human activities throughout giraffe habitat. But there is hope!

To gather scientifically based, accurate information and address contemporary threats to reticulated giraffes Giraffe reticulata (or Giraffe camelopardalis reticulata—the taxonomy of giraffe species and subspecies is currently being reviewed), San Diego Zoo Global (SDZG) and its international conservation partners have been working with local communities to preserve this iconic animal. “Today, two types of giraffe are listed by IUCN as Critically Endangered, while another two types are listed as Endangered, including the reticulated giraffe,” said David O’Connor, researcher, Population Sustainability, SDZG. While much of the giraffe’s plight has gone unnoticed, the tide is changing as more communities, agencies and organizations, and scientific disciplines are working together. From face-to-face surveys about giraffe use and perceptions in local communities to employing satellite tracking units on giraffes, researchers are illuminating the mysteries behind this towering herbivore.

June 21, 2020, the longest day of the year (in the Northern Hemisphere), is World Giraffe Day! How will you stick your neck out for wildlife?

June 21, 2020, the longest day of the year (in the Northern Hemisphere), is World Giraffe Day! How will you stick your neck out for wildlife?

Caring Community

In 2016, SDZG’s giraffe conservation program began with a strategic plan that has four key initiatives to benefit giraffe conservation. For any conservation program to be successful, it’s important that local people be supportive of the idea and included in the program. That’s why Twiga Walinzi (meaning “giraffe guards”), a community-led effort in northern Kenya to protect giraffes and reduce illegal killing of the animals, has been effective. Since Twiga Walinzi started, in the areas where they work, consumption and use of giraffe meat has declined significantly, from about 30 percent in 2016 to just 5 percent in 2019, according to surveys with local community members conducted by Twiga Walinzi. “In each survey, about 600 face-to-face interviews were conducted,” explained Kirstie Ruppert, Ph,D., Brown endowed researcher, Community Engagement, SDZG. Participants in four community conservancies were asked if they had eaten or used giraffe parts in the past 12 months, as well as their beliefs, “past, present, and future,” about giraffes and other wildlife. Responses were carefully translated and documented, elucidating this encouraging trend.

TEAMWORK

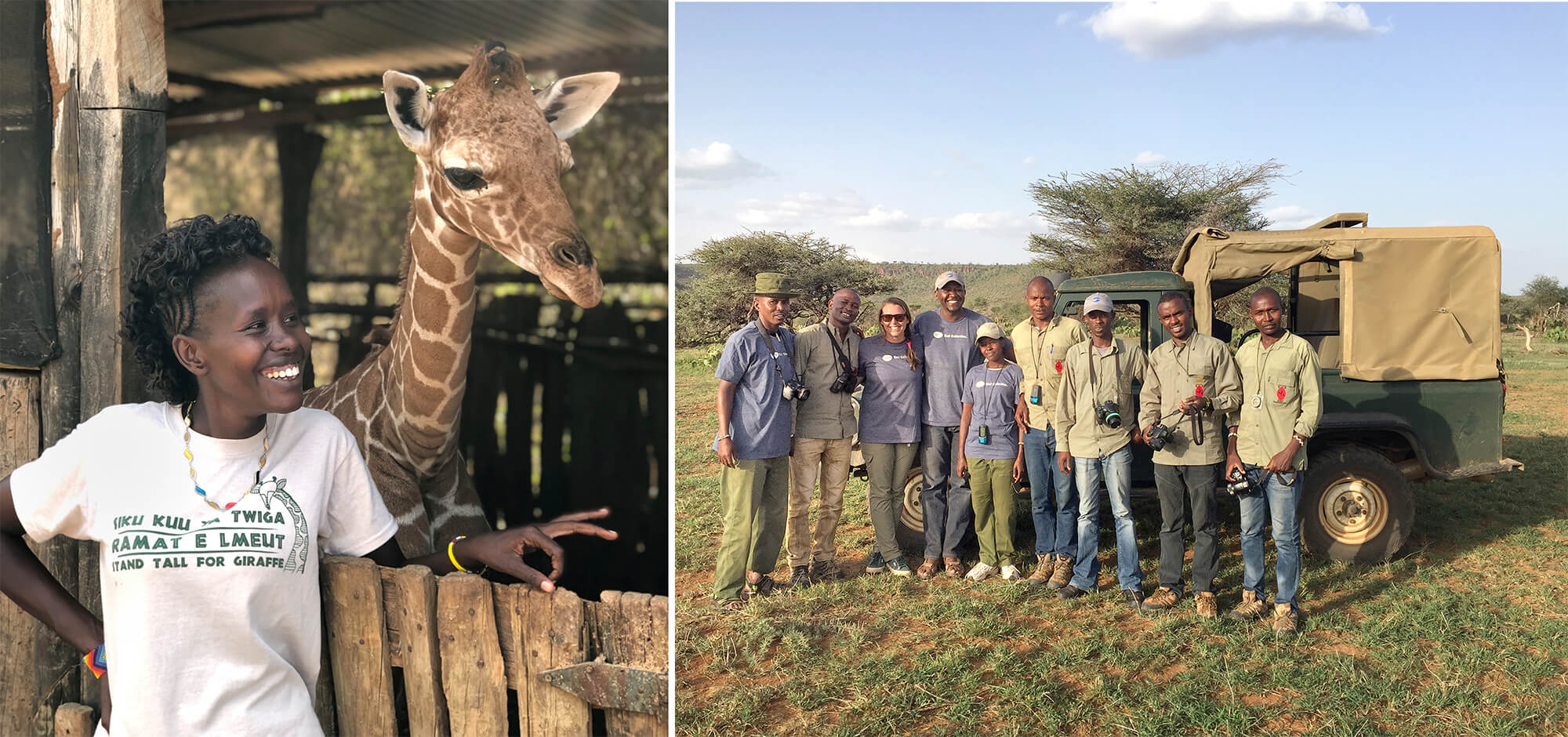

The Twiga Walinzi team track and document giraffes to ensure the health, safety, and protection of these iconic animals across northern Kenya.

The 16-person Twiga Walinzi team are from the communities in which they work, and they conduct all the research, conservation, and community activities, while acting as the all-important rangers. Since giraffes roam in and out of formal protected areas (mostly out)—often overlapping with people and livestock—community-based, multi-component efforts are crucial to lessening human impacts on giraffes. When people see the benefits of conservation-based jobs, they are more likely to speak up and protect their local wildlife. When community members see someone they know “guarding” giraffes, it becomes a form of social vouching, creating conservation norms for how people should act.

IT TAKES A VILLAGE

To safely capture and anesthetize a giraffe, collect samples, attach the tracker, and release the animal within a few minutes takes a team of conservation-committed experts (top). A giraffe is up and running after getting a tracker attached to its ossicone (above).

“When such norms are embedded into community planning and action, it shows that wildlife conservation is viewed as a good use of the land,” said Kirstie. “Now we want to maintain and expand areas where giraffe habitat is protected.” The project also entails improving existing schools, based on guidance from the communities. Desks, books, and even scholarships are funded, which can improve attitudes toward giraffes and wildlife in general. “We are proud of the decline in levels of giraffe consumption,” added Kirstie. Another measure of the success of the initiative is that Twiga Walinizi has been invited to work in another region of Kenya, where there have been reports of large giraffe populations and increased poaching levels. A pilot project is scheduled for this year. “We want to work where there’s the biggest impact, and move the needle in conservation,” said David. While building trust takes time, “results from being community based expand to being well received,” he added.

Click here to participate in Wildwatch Kenya, and help researchers sort through thousands of images taken by field cameras set up in northern Kenya.

Click here to participate in Wildwatch Kenya, and help researchers sort through thousands of images taken by field cameras set up in northern Kenya.

Collars and Collaboration

Despite giraffes being ubiquitous in pop culture, the situation in Africa is dire; little is known about their habits, range, or ecology. To get a clearer picture of giraffes and how they use the landscape, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF), along with SDZG and other partners, traveled through Africa to locate giraffes and attach satellite tracking units across giraffe species, in eight countries. The units are about the size of a deck of cards and are attached to one of the animals’ ossicones, the horn-like structure on its head. It’s a complex and challenging process to safely get a creature that is steadfast in its vertical existence on the ground and horizontal to place the trackers. But practice, collaboration, and expertise with a committed team made up of scientists, veterinarians, and rangers has made the work possible. The tracking units will show how much space the giraffes use, corridors needed to connect suitable habitat patches, migration patterns, habitat preferences, and how much time the giraffes spend in protected and nonprotected lands.

TECHNOLOGY AND TENACITY

SDZG and local community members work together to learn about how giraffes use the landscape.

Already, early data from the trackers has revealed some surprises. For instance, male and female reticulated giraffes seem to have very different home range sizes: a female explored about 97 square miles (250 square kilometers), while a male covered an incredible 483 square miles (1,250 square kilometers) during the same time period. “There will be further insights as more data download from the devices,” said David. Collars were also placed on livestock, like camels and cattle, which share the landscape with giraffes. Notably, some livestock traveled up to 124 miles (200 kilometers) to find fresh pasture during the dry season. Finds from this program show that connectivity for people and wildlife across the changing landscape is needed. Communities, conservancies, and conservationists are working together for a common goal, and it remains a tall, tall order.

How you can help

Your support goes a long way to help Twiga Walinzi protect giraffes in northern Kenya. Here’s an idea of what it takes to keep the program running.

Fund a Twiga Walinzi Team: $28,105 per year: $2,342 per month; $75 per day

Provide necessary field equipment for Twiga Walinzi: $5,000 per year; $417 per month; $313 per person

Twiga Walinzi student scholarship: $2,000 per year

Twiga tracker giraffe satellite tracking unit: $5,000 (includes attachment and 2 years’ satellite connection)

Ruko giraffe rewilding: $4,200 (reintroduction and translocation cost per giraffe)