Discovery of Parthenogenesis, or Asexual Reproduction, Is a First for the Species; and by Historic Confirmation Through Molecular Genetic Testing

SAN DIEGO (Oct. 28, 2021) – Conservation scientists at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance reported an extraordinary discovery this week in the Journal of Heredity, the official journal of the American Genetic Association, that could have rippling effects for wildlife genetics and conservation science. During a routine analysis of biological samples from two California condors in the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s managed breeding program, scientists confirmed that each condor chick was genetically related to the respective female condor (dam) that laid the egg from which it hatched. However, in a surprising twist, they found that neither bird was genetically related to a male—meaning both chicks were biologically fatherless; and accounted for the first two instances of asexual reproduction, or parthenogenesis, to be confirmed in the California condor species.

Additionally, the two dams were continuously housed with fertile male partners. So, this parthenogenesis discovery is not only the first to be documented in condors, but is also the first discovered through the use of molecular genetic testing, and the first in any avian species where the female bird had access to a mate.

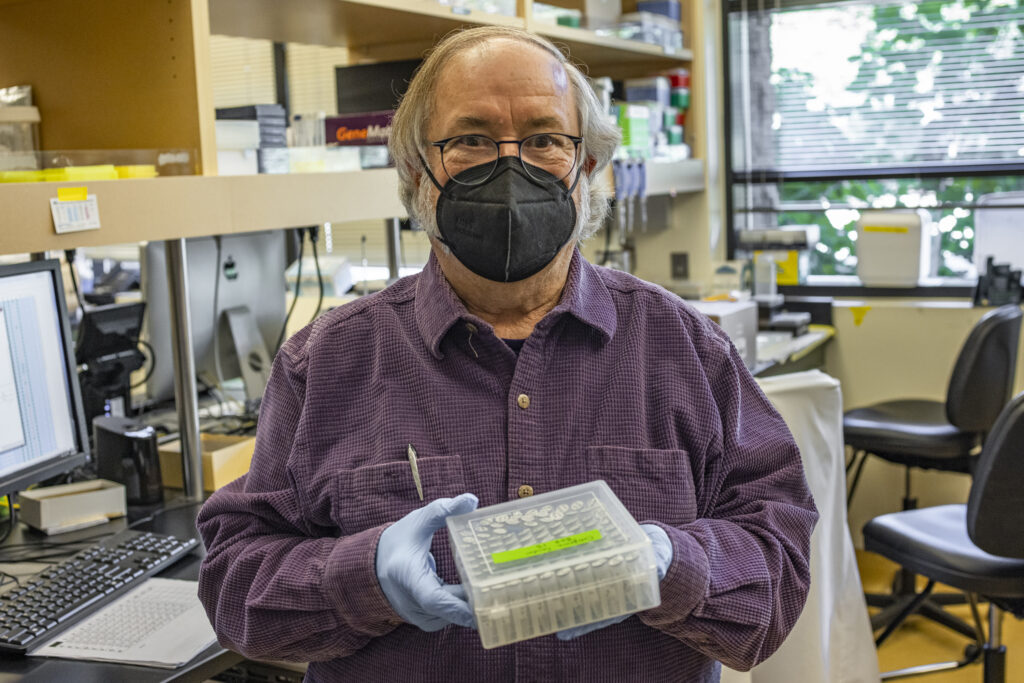

“This is truly an amazing discovery,” said Oliver Ryder, Ph.D., Kleberg Endowed Director of Conservation Genetics at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, who is co-author of the study. “We were not exactly looking for evidence of parthenogenesis, it just hit us in the face. We only confirmed it because of the normal genetic studies we do to prove parentage. Our results showed that both eggs possessed the expected male ZZ sex chromosomes, but all markers were only inherited from their dams, verifying our findings.”

Parthenogenesis is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which an embryo that is not fertilized by sperm continues to develop, containing only genetic materials of the mother. The resulting offspring are called parthenotes. While this phenomenon is well known to biologists, it is relatively rare in birds, and normally observed in females who have no access to males. The California condor parthenotes were produced by two different dams, each of which was continuously housed with a fertile male. Both of these females had also produced numerous offspring with their mates—one had 11 chicks, while the other was paired with a male for over 20 years and had 23 chicks. The latter pair reproduced two more times following the parthenogenesis.

“We believe that our findings represent the first instance of facultative avian parthenogenesis in a wild bird species, where both a male and a female are housed together,” said Cynthia Steiner, associate director for the conservation research division at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and co-author of the study. “Still, unlike other examples of avian parthenogenesis, these two occurrences are not explained by the absence of a suitable male.”

Historically, studying parthenogenesis in birds depended on careful observation that made it difficult to confirm, and the instances were confined mainly to domestic birds. For example, studies conducted in 1965 and 1968 identified parthenogenetic development in turkeys; and in 1924 and 2008, scientists noted the same in finches and domestic pigeons, although the eggs failed to progress to the hatching stage in the latter cases.

Fast-forward to today, researchers were able to confirm this novel finding at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance by leveraging comprehensive data collected throughout the successful and collaborative California Condor Recovery Program. For over 30 years, conservationists have conducted extensive genetics and genomics research, using samples of blood, eggshell membranes, tissues, and feathers to gather hereditary data from 911 individual condors. They were able to cross reference historical genetic records before confirming the outcome of this distinctive case of parthenogenesis.

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s conservation team believes that though these results represent only two documented cases in the condor population, the discovery could have significant demographic implications. Although one chick passed away in 2003 at age 2 and the other in 2017 at 8, the team plans on continuing future genotyping efforts in the hopes of identifying other parthenogenetic cases. “These findings now raise questions about whether this might occur undetected in other species,” Ryder said.

###

About San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is a nonprofit international conservation leader, committed to inspiring a passion for nature and creating a world where all life thrives. The Alliance empowers people from around the globe to support their mission to conserve wildlife through innovation and partnerships. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance supports cutting-edge conservation and brings the stories of their work back to the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park—giving millions of guests, in person and virtually, the opportunity to experience conservation in action. The work of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance extends from San Diego to strategic and regional conservation “hubs” across the globe, where their strengths—via their “Conservation Toolbox,” including the renowned Wildlife Biodiversity Bank—are able to effectively align with hundreds of regional partners to improve outcomes for wildlife in more coordinated efforts. By leveraging these tools in wildlife care and conservation science, and through collaboration with hundreds of partners, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance has reintroduced more than 44 endangered species to native habitats. Each year, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s work reaches over 1 billion people in 150 countries via news media, social media, their websites, educational resources and the San Diego Zoo Kids channel, which is in children’s hospitals in 13 countries. Success is made possible by the support of members, donors and guests to the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park, who are Wildlife Allies committed to ensuring All Life Thrives.