BY Nicholas Pilfold, Ph.D. and Kirstie Ruppert, Ph.D.

Leopard conservation requires a strategy as multifaceted as the species itself.

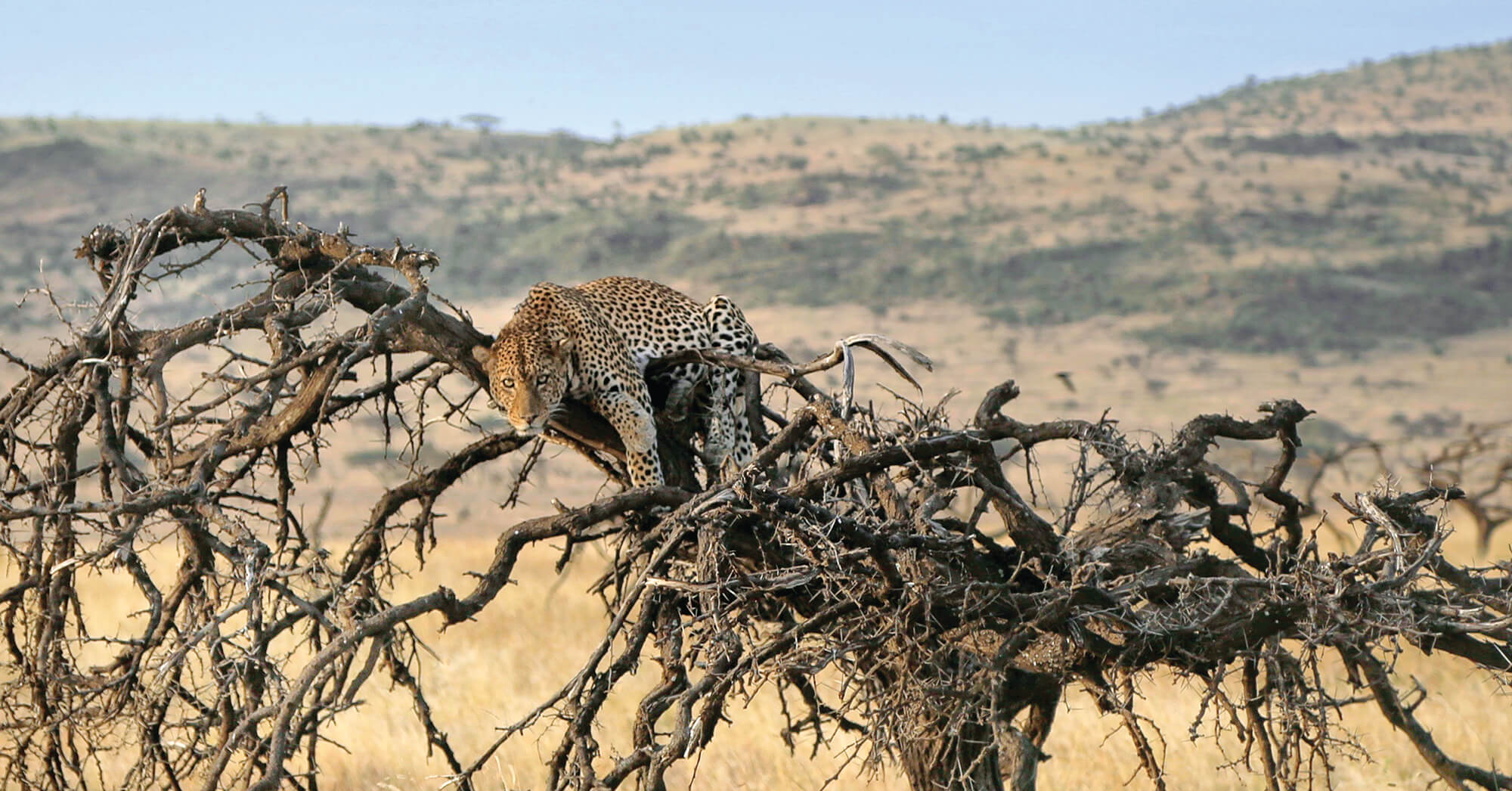

Majestic and highly adaptable, African leopards Panthera pardus pardus represent different things to different people. Some savanna communities may regard these charismatic big cats as nuisance predators, raiding livestock corrals for an easy meal. To others, they are a fashion muse, their stunning coat a continual source of inspiration for the runway. And the world of wildlife conservation considers the species an icon—the embodiment of the threats faced by all large carnivores in an environment of ever-increasing human encroachment. What a leopard is depends on one’s perspective, and in reality, each one of these multifaceted views plays a role in determining whether we save leopards from extinction.

Losing Ground, Gaining Support

Over the past three years, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Uhifadhi Wa Chui (Swahili for “conservation of leopards”) program has been working with our partners in Kenya at the forefront of a new wave of scientific inquiry to understand the enigmatic and, at times, maligned big cat. The conservation need for leopards is clear: in Africa, leopards have lost two-thirds of their historic range and are listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. Yet, little is known about their population numbers, as leopards have not received the same conservation attention garnered by the other large carnivores they live with. In Kenya, lions, hyenas, wild dogs, and cheetahs all have government-backed conservation action plans, while leopards do not.

The lack of conservation effort for leopards is not limited to Kenya; it spans across Africa, as leopards are thought to be highly adaptable, and thus not in need of conservation. Leopards can be found in a variety of environments, from deserts to thick tropical forests, from city streets to the most remote and rugged areas of the African continent. This ability to adapt is also supported by genetics, with a recent scientific paper suggesting African leopards have the most diverse genome of any of the big cats, as a result of not suffering historically from inbreeding or genetic bottlenecks as other big cats have. Historically, it seems leopards have always found a way to survive.

Location: Loisaba Conservancy and Mpala Research Center, Kenya.

Integrating Disciplines

While African leopards’ adaptation to change is impressive, their capacity to endure in modern times is ultimately limited by the threshold to which people are willing to live with them. Sharing the landscape with leopards is intertwined with both costs, including the losses of time, energy, and income enmeshed with livestock depredation; as well as benefits, derived from the role of leopards as part of functioning ecosystems and as a draw for wildlife-based tourism. Recognizing this spectrum of values and finding ways to practice conservation that reflects the needs of both people and wildlife will help us ensure that leopards persist into the future, and it is in this confluence that the Uhifadhi Wa Chui program pursues its conservation goals.

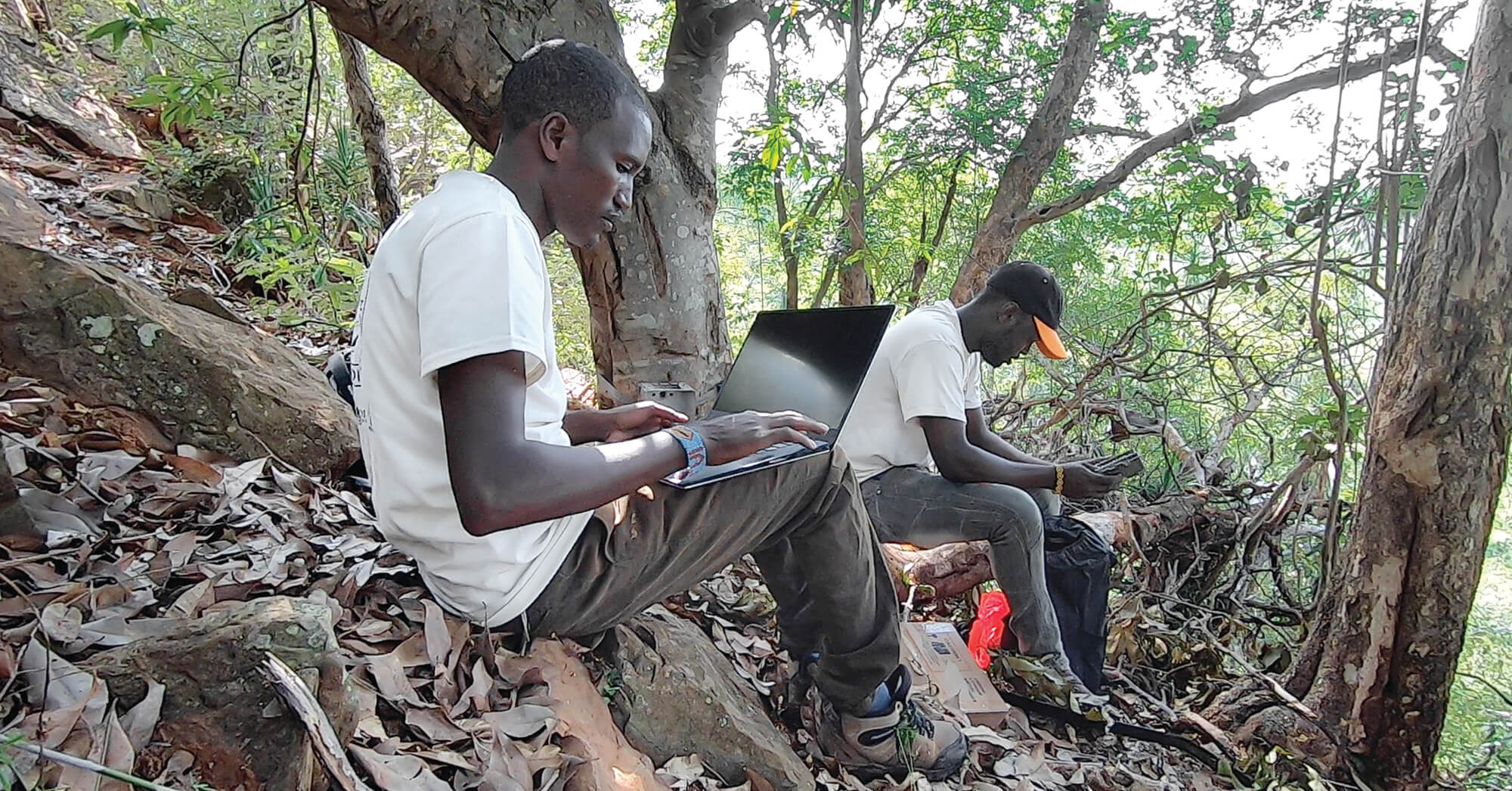

Those goals are twofold. First, to provide the information on the status of the leopard population in northern Kenya, while simultaneously advancing the science of population tracking. Second, to increase the human tolerance to coexisting with leopards by addressing livestock loss with local communities. To realize these goals, Uhifadhi Wa Chui is integrating ecological and social science with communities as our partners in conservation.

Tracking and counting leopards comes with challenges. The first is simply finding leopards, and this proved not an easy task, as leopards have survived in large part due to their ability to hide in plain sight. However, over the past three years, we have become very good at photographing leopards on remote cameras. As these cameras only view a tiny fraction of the study area, we have learned to see the landscape from the perspective of the leopard, focusing in on trees that leopards like to use to mark their territory, eat a meal or catch a catnap. Honing this ability has not only allowed us to track the population, which will soon result in the first-ever multi-year population assessment of leopards in Kenya; it has also revealed some incredibly rare black leopards living in our population. These melanistic individuals have become a source of inspiration, and garnered the attention of news media and documentary filmmakers alike.

Location: Loisaba Conservancy and Mpala Research Center, Kenya.

Cooperation on Track

In an effort to improve the tracking of leopards, we are embarking on a new study of leopard genetics. We are examining ways in which we can gather DNA samples from leopards in a passive manner, and use these samples to identify and count individuals. Our investigation so far focuses on collecting hairs left behind when leopards scent-mark trees. If the approach works, we can expand our population counts from local to regional areas, improving our understanding of leopard population dynamics.

Combined with efforts to find and track leopards, our pursuit for coexistence involves understanding the lived experiences of communities on the landscape. As herding families keep and move their sheep and goats, we needed to know when and where their livestock are most vulnerable to depredation, so we could start to work together to find solutions. Equally important is understanding what comprises tolerance for leopards, based on how local communities are interacting with them. Our early results suggest that the process of working together with communities on this problem increases tolerance for and participation in the conservation of leopards locally. We regularly receive feedback from community elders about the value of building this program with a commitment to listening in our search for sustainable solutions. The work in the communities has been a source of inspiration, even leading to the formation of one group, led by women who carry the leopard name as ambassadors for their conservation: the Chui Mamas.

Planning for the Future

Understanding what is needed to conserve leopards has been a journey of perspectives. It has led us into the homes of community members and into the steep and rugged landscapes leopards inhabit. The important work of combining the information to formulate a conservation action plan for leopards lies ahead. We have confidence that by including all perspectives gained through our cultivated relationships with Kenyan colleagues and community members, our science-based recommendations will be enacted and used to protect leopards into the future.

Nicholas Pilfold, Ph.D., is a population sustainability scientist for SDZWA; Kirstie Ruppert, Ph.D., is a community engagement scientist for SDZWA.