BY Donna Parham

Photography by Ken Bohn

If you want to spot an orangutan in the wilderness of Borneo or Sumatra, you’ll have to look up. These shaggy red apes spend most of their life in the trees, feasting on ripe fruit and climbing, clambering, walking, and swinging confidently from branch to branch. With arms longer than their body; long, strong fingers; and grasping toes, life in the trees is a breeze. Females even give birth high in the rainforest. At the San Diego Zoo, the orangutan’s habitat includes climbing structures that are joined by ropes and cargo nets, and vertical “sway poles” that gently bend like tree branches and help create aerial pathways through the habitat.

FOREST PEOPLE

The name orangutan means “people of the forest.” These apes live in tropical and swamp forests on the Southeast Asian islands of Borneo and Sumatra. They are the world’s largest arboreal mammal, and the only great apes in Asia—all other great ape species live in Africa. (Photo by Anup Shah/Getty Images)

Without predators like clouded leopards, Sumatran tigers, giant pythons, and crocodiles to avoid, orangutans at the Zoo are also quite comfortable on the ground. They spend time in and around rocky caves and man-made “termite mounds” that are often filled with tasty treats for the orangutans to retrieve. In Sumatra, orangutans ignore other primates, but at the Zoo, they often interact with the siamang family that shares their habitat. You might even get eye to eye with an orangutan that’s made itself at home up close to the habitat’s glass. And if you think they’re watching you, you could be right. They might want to show off their newest enrichment item, such as a burlap sack—or they might just want to watch you!

TOOL USERS

On Borneo and Sumatra, orangutans sometimes strip leaves from twigs and use them to reach into holes for termites. At the Zoo, orangutans do the same thing, when their care specialists hide treats like yogurt and mustard in artificial termite mounds.

“The excitement that a guest has when they watch the orangutans and their natural behaviors—whether here at the Zoo, or at home watching on Ape Cam—is the same stuff that excites us,” says Tanya Howard, the Zoo’s orangutan care specialist. “Seeing those positive interactions—with each other and with the siamangs that share their habitat—is a large part of what drives our day, and we are always looking for what we can do to make those behaviors as frequent as possible.”

LOTS TO LOVE

At the Zoo, orangutans share their habitat with siamangs. The apes’ natural behaviors and interactions are endearing and often amusing, or sometimes downright hilarious. It’s hard not to imagine that an orangutan caregiver’s job would be a ton of fun. “The fun part of it is very real!” Tanya says.

All other apes and monkeys live in social groups, but orangutans are a little different. Experts used to think they were solitary, but recent studies tell us more. Where food is abundant, orangutans are a bit more social. They hypothesize that the orangutans’ semi-solitary social system may have evolved as a result of their diet—ripe fruits are scattered over a wide area, so orangutans also have to spread out, so they can all get enough food. In zoos, orangutans don’t have to spread out to forage, and they often do well in socialized groups. Tanya has cared for the Zoo’s orangutans since 2010, and she admits that she considers the orangutans “the best animals in the Zoo.” Here’s a look at the four orangutans in our group.

ONE OF A KIND

With his thick cheek pads, pendulous throat sac, and long hair, mature male Satu is easy to recognize. He is the only adult male orangutan at the Zoo. In the forests of Sumatra and Borneo, adult male orangutans avoid each other.

THE BIG PATRIARCH

Whether on Sumatra or on Borneo, cheek-padded adult male orangutans don’t care for company. Typically, one of these adult males is alone unless he’s consorting with a female or fighting with another male. But at the Zoo, it’s not unusual to see adult male Satu interacting with—or at least, patiently tolerating—the other apes in the habitat, especially the young and playful, like seven-year-old orangutan Aisha and two-year-old siamang Sela. “He’s no longer a kid, but he will interact with Aisha and Sela in what could be considered play behavior,” says Tanya. She described Satu as “the most laid-back male I’ve ever worked with,” even allowing rambunctious Sela to play with his long hair. “His personality didn’t change when he developed facial pads,” says Tanya. “He wants to dismantle things all the time—that’s an orangutan for you!”

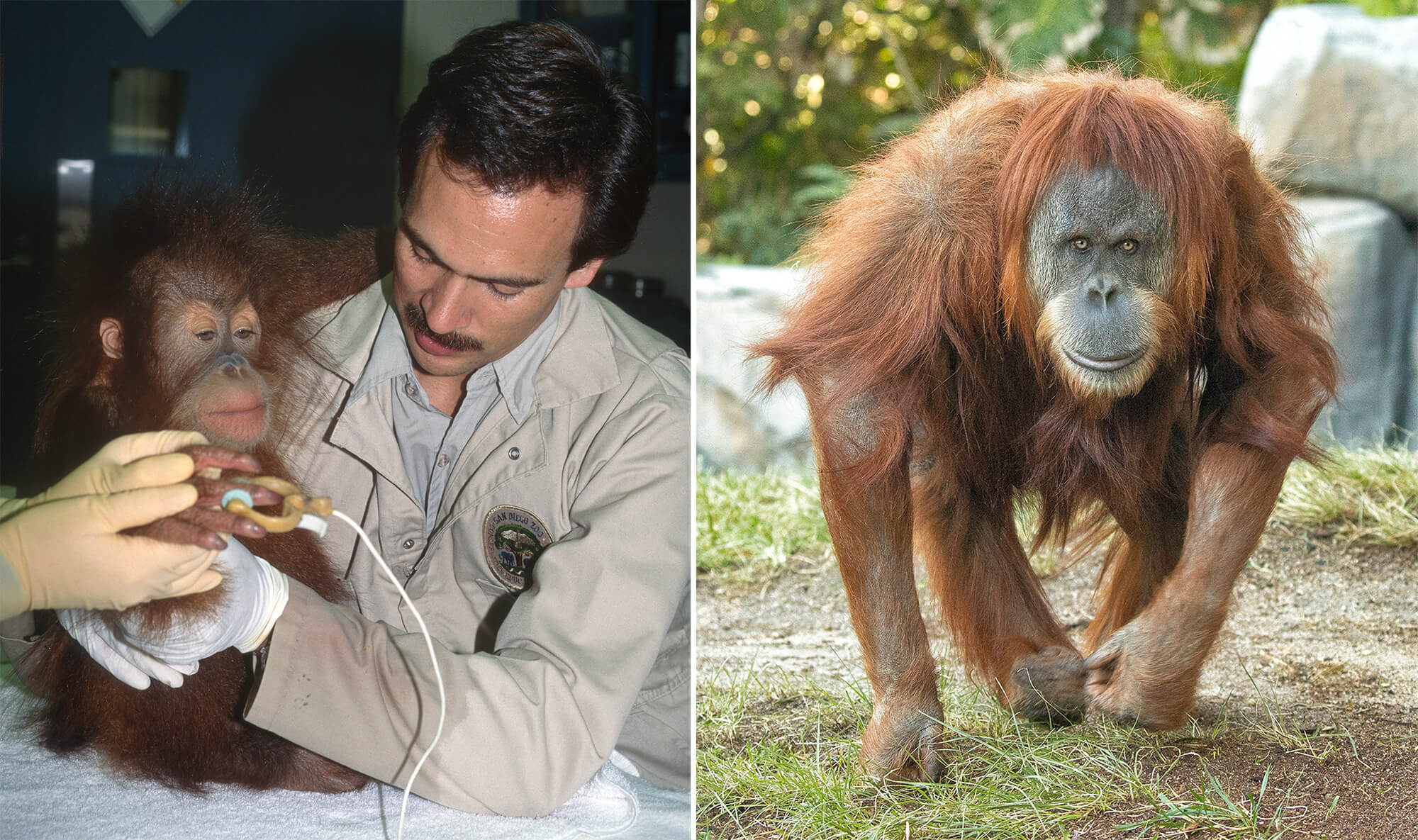

EVERYBODY LOVES KAREN

Thanks to expert medical attention and lots of loving care, Karen made an amazing comeback from a life-threatening, congenital hole in her heart. You might find Karen delighting Zoo guests by observing and interacting with them.

THE BELOVED SURVIVOR

The only member of the orangutan group to be hand-raised at the San Diego Zoo as an infant, spunky Karen survived a widely publicized open-heart surgery in 1994, and she remains a guest favorite. She may be small, but she has a big personality. You might spot her rolling on the ground or twirling around the sway poles. The veterinary staff keep a close eye on Karen, and she gets a full cardiac workup with her routine, preventive maintenance exams. The 28-year-old is thriving. “Her heart is deemed perfect at every exam,” Tanya says. She advises guests to look for Karen playing on the ground or up in the hammocks.

ADULTS KNOW BEST

Indah knows just how to be an adult female orangutan, and she does it well. In the forests of their native Borneo and Sumatra, mother orangutans teach dependent offspring the location of fruiting trees and how to eat various fruits. Orangutans have the longest dependency period of any mammal, and a mother’s attention and care is critical to the success of their offspring.

THE CARING FEMALE

Female Indah may seem more aloof than the other orangutans, generally preferring the treetops and climbing structure to the ground. Lately, though, Tanya has observed her coming down and approaching the glass. The 34-year-old is the capable dam of Aisha as well as 17-year-old Cinta, a male who now resides at the St. Louis Zoo and is a sire himself. “Indah has grown more confident recently,” says Tanya. “She and Aisha make a nest every night, up in the climbing tree.” Orangutans have the slowest breeding rate of all mammals, bearing a single infant only every seven or eight years, and Indah is still nursing and mothering Aisha.

GROWING UP

Zoo visitors and Ape Cam watchers have watched Aisha grow from a precious infant to a self-assured juvenile. As seven-year-old Aisha becomes an adult, she’s growing more and more independent. Over the years, we’ve celebrated 30 orangutan births at San Diego Zoo Global.

THE RAMBUNCTIOUS KID

Tanya describes seven-year-old Aisha as “brave and rambunctious, with a lot of personality.” During the seven or eight years that young orangutans stay with their dams, they learn where in the forest to find fruit, how to build a nest, and other survival techniques before they set off on their own. The bond between Indah and Aisha is strong. Although Aisha eats food that the other orangutans eat, she’s still nursing, too, which is typical for orangutans.

Like most mammal offspring, young orangutans are more active and social than adults. “She’s getting bigger and gaining weight, but she’s still allowed to get away with everything,” Tanya says. You often see Aisha playing and interacting with the other orangutans and siamangs, especially young siamang Sela.

HELP FOR ORANGUTANS

The AZA Orangutan SAFE Programs brings together the collective expertise within AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums to conserve orangutans. (Photo by USO/Getty Images Plus)

IMPERILED ASIAN FORESTS

In their native Indonesia and Malaysia, orangutans are Critically Endangered, and they face some serious threats to their survival. Palm oil plantations have taken over much of their forest habitat, and poachers target young orangutans for the illegal pet trade.

San Diego Zoo Global supports the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ (AZA) Saving Animals From Extinction (SAFE) Orangutan Program. The goal is to protect and restore wild orangutan populations and their habitats through public engagement, funding, and field work that focuses mainly on habitat protection, rescue and rehabilitation, and capacity enhancing. Together, we are working to keep healthy populations of these beloved, shaggy, red apes high in the trees on Borneo and Sumatra.

To find out how you can help San Diego Zoo Global conserve wildlife, visit endextinction.org.