BY Lisa Townsend

Photography by Lisa Townsend and Jen Tobey

In September 2016, three San Diego Zoo Global staff members representing animal care, conservation research, and education traveled to New South Wales, Australia to participate in koala field research: Lindsey King, a senior keeper at the Zoo; Jennifer Tobey, population sustainability researcher with San Diego Zoo Global’s Institute for Conservation Research; and me, Lisa Townsend, a senior educator at the Zoo. We joined Dr. Kellie Leigh, director of Australia’s Science for Wildlife organization, and her amazing team of climbers, postgraduate students, and volunteers, to find and map low-density koala populations in Wollemi National Park within the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

SERVING HIS COMMUNITY

This koala project participant will help inform local conservation efforts.

Although koalas are not often seen on the high-altitude ridgelines of the Blue Mountains region, they were once abundant in the valleys—historical records show advertisements of hunting opportunities back in the days of the koala fur trade. Since then, koala numbers have dropped dramatically: koalas are vulnerable to extinction across much of their range. Once thriving, koala numbers are now as low as 300,000 adult individuals.

Following the 2013 bushfires in the Blue Mountains region, koalas were heard and spotted in parts of the mountains in which they had not been known for decades. Driven out by the ferocity of the fires, the ultimate death toll on the region’s koala and general wildlife populations will never be known. However, the fires did alert researchers to the surprising presence of koalas. Science for Wildlife is working to find these koala populations. Once documented and mapped, the information will be shared with land managers, rural fire services, and community groups to protect and restore koala habitats.

Mountain Lagoon Koalas

Our first research site was in Mountain Lagoon, where there are both national park and private lands making up the koalas’ territorial range. This is a verdant countryside, where pastures give way to various densities of eucalyptus forest, dotted with small pools and rock outcroppings. There are farmhouses, barns, cow paddocks, and even curious livestock. The pastoral landscape and cool weather provided a picturesque and comfortable backdrop for our fieldwork. We had four short winter days to locate and retrieve collars from five male koalas in the study: Uno, Zeus, Pine, Zen, and Jac.

“Uno” Fine Day

The first koala located was “Uno,” a robust boy with a solidly defended territory. The signal from his radio collar led us to a lightly forested area off of a dirt road at the edge of the national park. Graduate student researchers Nicole and Brie had been tracking him and other koalas every weekend for the better part of a year: hiking through the bush, tracking the collared animals with an antenna, and marking the trees where they were found. However, this day was different: the plan was to bring Uno to the ground and retrieve his collar. While everyone else seemed pleased with his placement and the proximity of the nearest tree for our climbers, I was standing at the base of his tree, desperately trying to find him among the leaves. It’s harder than it seems: in the photo above, he’s in the center of the circle. You can imagine how hard that would be to spot from the ground!

VITAL INFORMATION

Top: Marty hangs Uno from the field scale so the team can record his weight. Bottom: Dr. Kellie Leigh, Lisa, and Lindsey examine, score, and record Uno’s physical condition.

Marty and Emily, the climbing team, worked methodically to make sure he was safely brought down the gum tree. By gently shaking a yellow flag above his head, he was motivated to move lower and lower down the trunk to get away from it, unconcerned with the folks standing below. Once he was about a meter from the ground, he was covered with a cloth sack to keep him calm and secure. Uno was then weighed, measured, checked for injury and disease, and then his collar was removed. One way to measure body condition is by feeling for a bony ridge on the koala’s scapula (shoulder blade). It is well-muscled in a healthy koala, but protrudes more as they lose condition.

NUMERO UNO!

His radio collar seems to have served him well as armor. The dings and dents recount territorial combat.

The entire exam happened in several minutes. Found to be fit, and now collar-free, Uno was released. He did not run away or quickly dart up the tree: rather, he slowly climbed with his back to us. At about three meters up, Uno stopped and looked at each one of us. No grumbling, crying or bellowing, just stoic contemplation. Then, he continued to ascend into the canopy. The radio collar, which is retrofitted with a breakaway loop for safety, showed that this big guy had been challenged for his territory—his collar’s hardware bore some impressive battle scars. However, since Uno was still there, he had clearly been the victor.

Dogging Animals

While we were in the area, Kellie took time to do a training session with Badger, her Australian shepherd. Badger is a detection dog that finds spotted-tailed quolls (a carnivorous marsupial), and he is also cross-trained to detect koalas. His incredible nose can uncover a morsel of degraded koala scat that his handler has hidden in the leaf litter. When he alerts Kellie to the find, she rewards him with a treat. One recovery exercise turned out to be unexpectedly accurate—Badger alerted Kellie to one of Uno’s resident female koalas sleeping nearby.

Clambering for Collars

I had never fully grasped the skill koalas possess to negotiate rough terrain while moving through their territory, but I deeply appreciated their dexterity over the course of the next three days, as we moved through chest-high bracken, scrambled over rocks, and traversed the steep ridgeline, to retrieve the collars of all five koalas. Zeus, so robust he was named for the Greek god, was easily found in a slender gum tree aIongside a cow paddock.

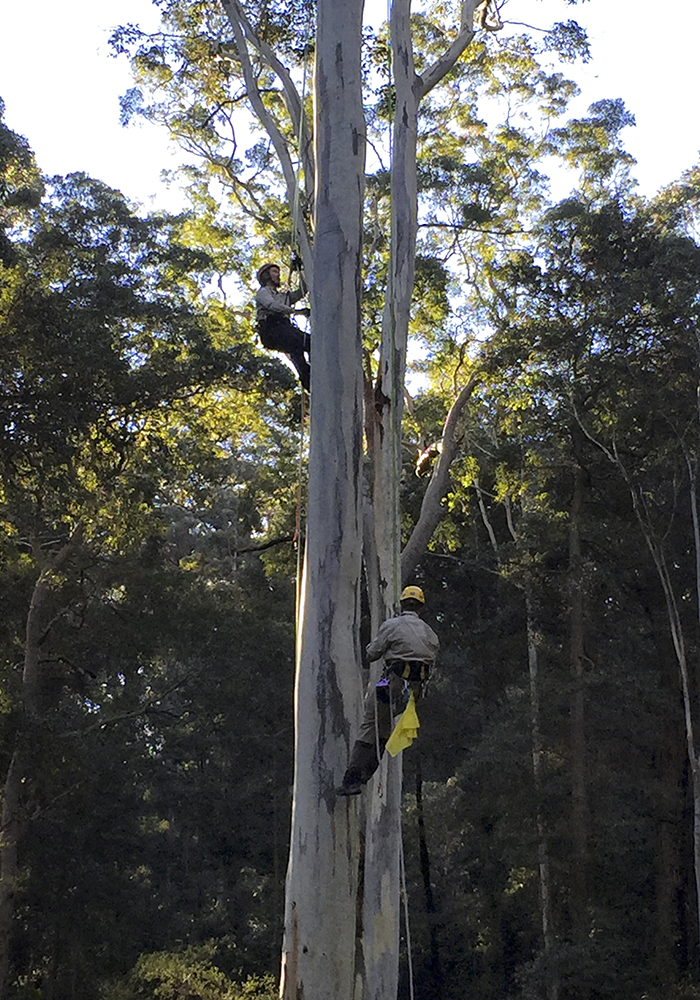

LOFTY ASPIRATIONS

Emily and Marty ascend toward “Zen.”

Pine, named after the conifer in which he was originally discovered, was in a turpentine tree off of a fire road. Zen, although tranquil himself, provided the climbers with a harrowing recovery near the top of a huge, 60-meter-tall eucalyptus (pictured above). Our last collar recovery was by far the most challenging: it took us five hours of beating the bushes to find Jac!

Colo River Koalas

Finding a koala by following the faint ping from a radio collar is difficult, but spotting a koala without the aid of said radio collar is nearly impossible. Our second site was along the Colo River, which literally translates to “Koala River.” The upper Colo River location is a valley in Wollemi National Park, accessed through private ranches. Science for Wildlife has a website where citizen scientists can report koala sightings to inform the search grid. Here, we had close to three dozen volunteers dedicated to finding a population of koalas scarcely seen and heard by local residents.

CLAWING THEIR WAY TO THE TOP

His sharp, curved claws make easy work of scaling this tree. previous: Koala tracks aren’t found on the ground, this tree trunk is well traveled.

Volunteers were introduced to the protocols and given some handy tips for koala spotting: move slowly and look through the trees, all of the trees, and keep your eyes peeled for scat on the ground, which can give you a direct line up to a koala. Also, scratches and gouge marks along the trunk of a tree are encouraging.

NICE TO MEET YOU

After his collar was removed, Uno was in no hurry to leave. He slowly moved up his tree, stopped and then considered each one of us. (Videography by Lisa Townsend)

I See You

We had early success; volunteer Robert spotted a koala on a eucalyptus bough arching over the trail. Most of the group continued moving to our base camp, to alleviate any unnecessary stress during the koala collection, but as it turned out, our new koala research participant was unfazed by the entire process. He remained calm, alert and quiet while being examined, collared, and ear tagged. In fact, he was so cool about the whole thing that he was dubbed “Cucumber.” The trunk of Cucumber’s tree was covered with scratch marks, indicating that this was a favorite place for surveying his territory. Over the next five days, we scoured the river’s edge and hiked the ridges, but our efforts yielded only one more collar deployment: handsome George. Through the ensuing Australian summer and fall, eight more collars will be deployed.

LOOKING OUT FOR KOALAS

The ground team watches a new research participant return to his treetop sporting a new radio collar.

Although the San Diego Zoo team may not be on the ground with eyes in the trees year round, our hearts are always with our mates in the Blue Mountains. The San Diego Zoo’s Koala Education and Conservation Program supports Science for Wildlife’s Blue Mountains Koala Project, and the San Diego Zoo koala colony is currently represented in 14 North American and European zoos. Through our loans of this iconic species, the San Diego Zoo has been able to educate millions of guests on the importance of understanding and protecting koalas and their unique habitat. Habitat loss, disease, and climate change are just a few of the challenges that threaten the stability of koala populations in Australia. The participation of partner zoos provides important education to zoo guests, and valuable support to boots-on-the-ground koala researchers who are fighting to save this species for future generations.