BY Donna Parham

For the first time in seven years, California condors from the US conservation breeding program are once again Baja bound.

If the idea of a trip to Mexico conjures up images of sun-splashed beaches, you might be surprised to find yourself breathing the crisp, cool, pine-scented air in the rugged mountains of Sierra San Pedro Mártir National Park.

Just 150 miles from San Diego (as the crow—or condor—flies), the 180-acre Sierra San Pedro Mártir (SSPM) National Park lies midway between the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Cortez, in Baja California, Mexico. It’s home to native wildlife like bighorn sheep, mountain lions, woodpeckers, golden eagles, and a small but thriving flock of California condors. The condor flock in Baja California began with birds that hatched in managed care and were introduced to SSPM by US and Mexico wildlife managers and biologists. “We introduced condors there every year for 10 years or so,” says Ignacio (Nacho) Vilchis, Ph.D., associate director of recovery ecology for San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA). As the birds reached adulthood, they found mates; and eventually, some parents started fledging their own chicks.

Temporary Turbulence

Alas, in 2015, the smooth operation abruptly halted due to several unforeseen factors, including turnover within governmental agencies in Mexico and changes in export/import regulations of both countries. As a result, from 2015 to 2022, no birds moved across the border. “We were at a standstill,” says Nacho. “Many of the changes in Mexico’s agencies resulted in a loss of institutional knowledge.” When Mexico’s division of endangered species became the responsibility of the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, or CONANP), Nacho says, “We had to start from scratch.” After a huge collaborative effort with CONANP, everything is now aligned. In April last year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), CONANP, and SDZWA moved two condors across the border.

Feeling at Home

Introducing condors to the native habitat is a cautious process. For six months or more, juvenile condors fly, roost, and interact within the protection of an enormous aviary, constructed around tall pine trees. As young birds get accustomed to their new surroundings, biologists provide food. They also put food outside the aviary, which attracts the local condor flock, as well as other scavengers. “Condors are super hierarchical,” Nacho says.

“The new birds learn the pecking order of the flock before being released. And, when scavenging predators show up for the free food, the condors also learn what to be afraid of—while they are still safely within the aviary.”

The Beauty of Baja California

Persistence in re-establishing the California condor introduction site in Baja California is about more than just expanding the range of these endangered birds. “Baja California is one of the best available habitats for condors,” Nacho says. “There’s much less hunting, so there is far less lead in the environment.” That makes the condors in Baja California less susceptible to lead poisoning—the number one cause of mortality in free-flying condors in the US. (Condors ingest lead fragments when they eat the remains of wildlife shot with lead ammunition.)

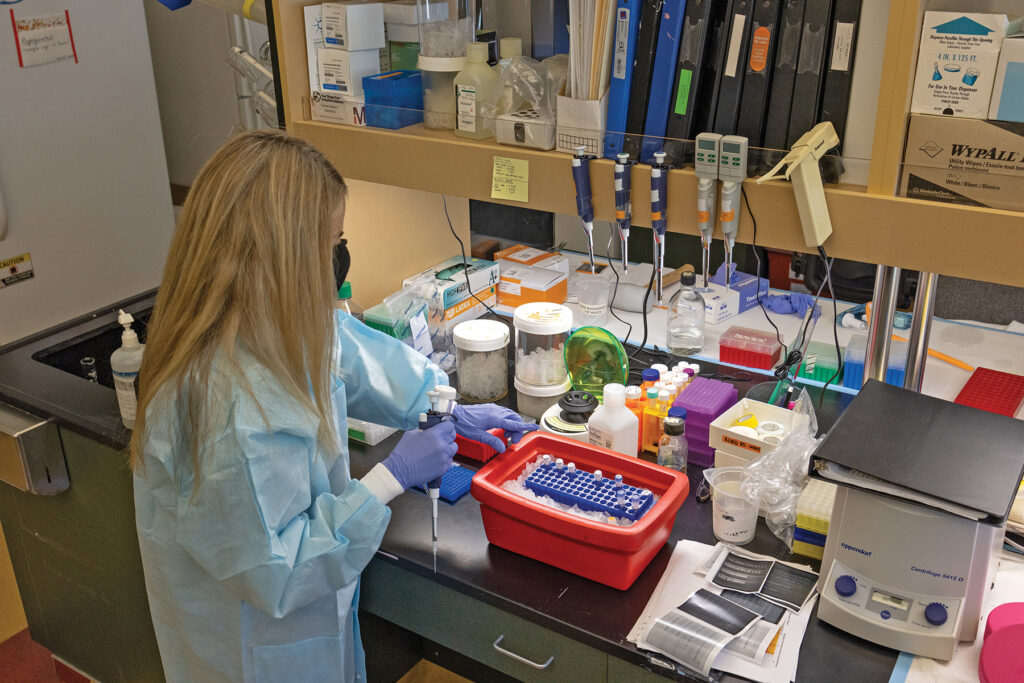

Other contaminants are far less common in Baja California, too. Nacho was part of a team of conservation scientists who investigated the presence of contaminants in stranded marine mammals—an abundant source of food for condors in both California and Baja California.¹ By comparing sources of possible food from both areas, they found that stranded marine mammals from California had larger presence of contaminants like mercury, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and the breakdown products of DDT, versus stranded marine mammals from the Gulf of California. Their findings back research showing that condors can ingest contaminants when they feed on the carcasses of marine mammals that have accumulated these persistent toxins. Information like this can be important when planning condor reintroductions.

Nacho is looking to a bright future for Baja California’s condor population. “We are hoping to move two more condors to the Baja California introduction site this spring, and another four or five per year for the next three years,” says Nacho. The latest Baja California reintroduction is a testament to the persistence of SDZWA conservation scientists, along with our partners in the California Condor Recovery Project and the government of Mexico.

Who Goes Where?

Conservation biologists determine which condor chicks will eventually be reintroduced, and where. “They determine the genetics of every chick that hatches in managed care and calculate the mean kinship [how related a bird is to all the other condors] for each of them,” explains Nacho. “They also take into account sex ratio and logistics such as transportation.” Historically, juvenile birds selected for introduction at the Baja California site have come from the propagation program at the Safari Park.

California condors are reintroduced when they are about two years old. By that time, they have spent a year or so among other condor fledglings in a remote socialization habitat—isolated from human activity—where they learn how to interact with each other. To encourage them to avoid human activity, food enters through a chute in the wall, and pools are drained and rinsed from the outside.

40 YEARS OF

—CONDOR CONSERVATION—

at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

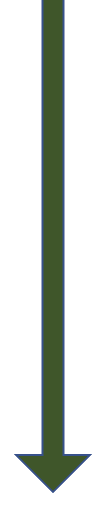

1983

Eggs rescued from condor nests are incubated and hatched at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. Over the next two years, SDZWA incubates, hatches, and raises a total of 12 condors.

1987

California condors are Extinct in the Wild. There are 27 at the Safari Park and the Los Angeles Zoo: 10 rescued from the native habitat, and 17 that were reared in managed care.

1988

“Molloko” hatches—representing the first successful mating, egg-laying, and hatching of a California condor in managed care, at the Safari Park.

1992

The first California condors raised in managed care (from rescued eggs) are reintroduced in California’s Los Padres National Forest.

2003-2004

The first wild-hatched chicks of reintroduced birds fledge, in Arizona and California.

2019

California’s Ridley-Tree Condor Preservation Act takes effect, requiring the use of nonlead ammunition when hunting wildlife in California.

TODAY

Your support makes these collaborative and cutting-edge conservation efforts possible, and together we’re restoring California condor populations in their native range.

Discover how you’re making a difference for local wildlife and ecosystems through our Southwest Conservation Hub.

¹ “Assessing Marine Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in the Critically Endangered California Condor: Implications for Reintroduction to Coastal Environments,” is published in Environmental Science and Technology, May 17, 2022. Our science team, including Ignacio Vilchis, Ph.D., Christopher Tubbs, Ph.D., and Rachel Felton, were part of the research team that led this study; along with San Diego State University scientists, in collaboration with Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada and the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.