Zoo InternQuest is a seven-week career exploration program for San Diego County high school juniors and seniors. Students have the unique opportunity to meet professionals working for the San Diego Zoo, Safari Park, and Institute for Conservation Research, to learn about their jobs, and then blog about their experience online. Follow their adventures here on the Zoo’s website!

All around the world, wildlife is becoming endangered due to poaching, habitat loss, and environmental pollution. One of the lesser known ways scientists contribute to the conservation of wildlife is through the field of reproductive physiology. Reproductive scientists utilize in-vitro methods, measure environmental factors, and study hormones that influence when and if reproduction can take place. Reproductive scientist, Mr. Tubbs, is essential for the conservation of species by ensuring animals reproduce to help increase their declining populations.

Christopher Tubbs is the Associate Director of Reproductive Sciences at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. Mr. Tubbs has worked at the Institute for over 13 years, and plays a vital role in the ongoing conservation efforts for white rhinos, California condors, and more. Earning his bachelor’s of Zoology at the University of Florida, and his doctorate in Comparative Endocrinology at the University of Texas at Austin, Mr. Tubbs joined the Institute’s team in 2007 as a postdoctoral associate. Fascinated with animals, and dedicated to the study of hormones, he is on the front lines of how we take care of not only our wildlife here at the Zoo, but also the animals in our own backyard.

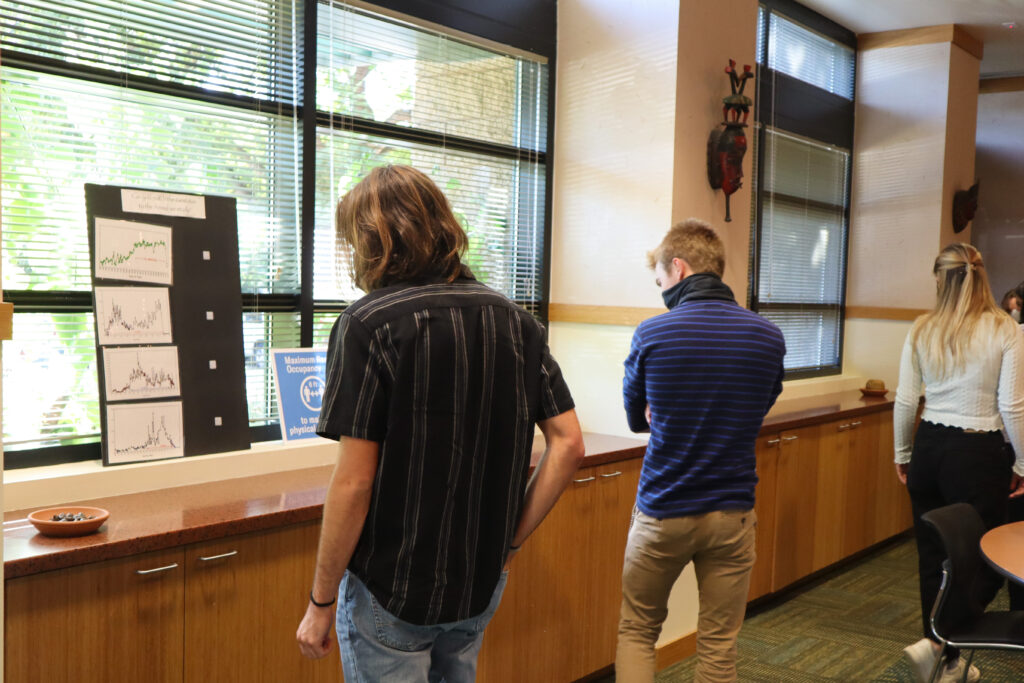

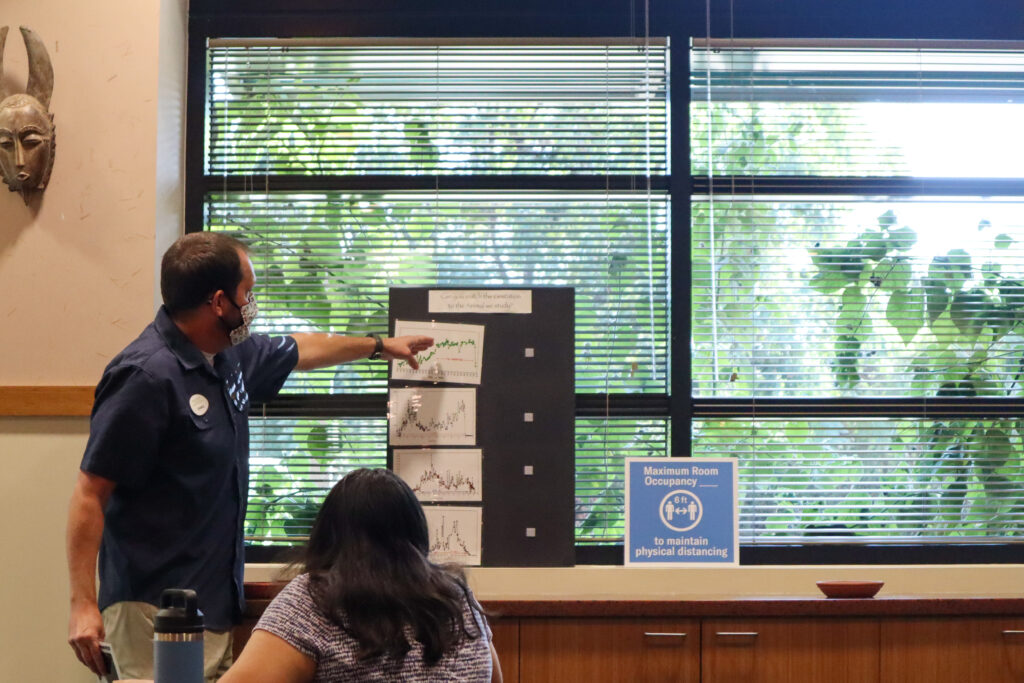

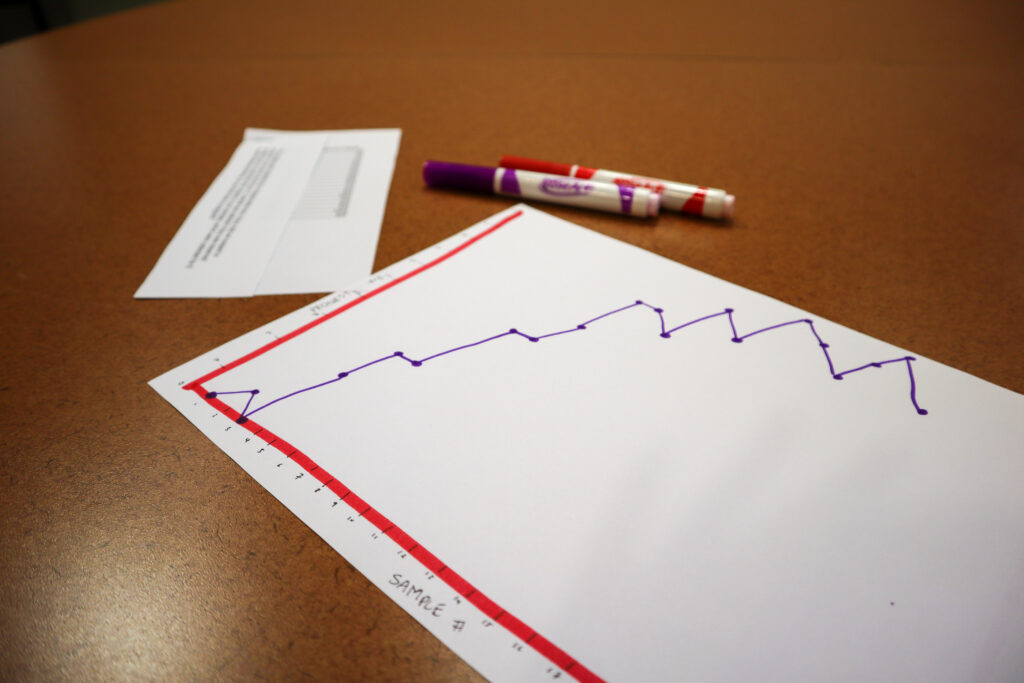

Mr. Tubbs’ job revolves around evaluating the reproductive status of animals. He does this by examining their levels of hormones, which are chemical messengers that are produced in glands and travel through the bloodstream to their target locations. They then bind to protein receptors to trigger specific processes to take place. For example, the “stress” hormone cortisol travels through the blood and binds to the receptors in heart tissue, triggering a signal that causes the body’s heart rate to increase. For Mr. Tubbs, hormones are like tools to determine internal information or problems that occur in animals. His current project is tracking the reproductive statuses of the female southern white rhinos at the Safari Park and Rhino Rescue Center. Because rhinos don’t particularly like getting their blood drawn, Mr. Tubbs collects data from an alternate source: rhino feces, which is luckily never in short supply! Through the feces, Mr. Tubbs and his team measure the rhinos’ levels of progesterone, a pregnancy regulating hormone. The rhino feces are then sent through a solvent in the lab that extracts the progesterone hormones and leave other unneeded material behind. Mr. Tubbs then puts the progesterone through a process called radioimmunoassay, which then allows him to finely identify the amounts of progesterone. Lastly, he records the data in graphs. The overall rise and fall of the data points gives Mr. Tubbs and his team a picture of the rhinos’ progress in ovulation and pregnancy.

While much of Mr. Tubbs’ job is spent in a lab, there are opportunities for field research, which is one of his favorite aspects. Several years ago, Mr. Tubbs’ and his postdoctoral assistant Candace, got to visit Kruger National Park in South Africa. During their ten day stay at a research camp, they had the opportunity to drive around the area viewing animals in their natural habitat, a very unique experience that he spoke fondly of. Another enjoyable part of his job is the constant learning, problem solving, and critical thinking. He mentions how his job is akin to a puzzle, one that he enjoys solving. For example, one problem troubling wildlife care specialists and scientists were the infertility levels of southern white rhinos in managed care facilities. Mr. Tubbs and his team discovered that the issue was a result of an imbalance in phytoestrogens in rhino diets. As a result, most phytoestrogens have since been removed from the rhinos’ diets and we have seen the effects in successful rhino births.

The obvious way Mr. Tubbs contributes to wildlife conservation, is by focusing on the environmental impacts on reproductive health. As we’ve already learned, his research has led to a more sustainable approach to rhino care, increasing the reproductive success among the species. He supports both facilities in their reproductive initiatives to save species of concern. Besides working at the Institute studying hormones, Mr. Tubbs serves as a member of the International Rhino Foundation and holds a board of directors position within the International Rhino Keeper Association. Both of these organizations are dedicated to stabilizing rhino populations through a cooperative effort of different fields like genetics and reproductive physiology. By supporting associations like these, you can help the efforts to save the rhinos. As a consumer, you can also make a conscious decision about your purchases. Even one small change can make a great impact on saving plants, animals, and habitats.

Mr. Tubbs doesn’t only research how different compounds affect the reproductive system of rhinos, but other physiological factors of wildlife as well. The California condor is listed as critically endangered but from conservation efforts their population is increasing. As scavengers, they are a fundamental part of many ecosystems due to their role as decomposers. One of the main threats to these birds is lead poisoning. In their terrestrial environments, they ingest lead through decomposing animals that had been shot by lead bullets. In order to counter this risk, the Ventana Wildlife Society relocated condors into Big Sur in 2017 where their main food source would be dead marine animals. Although the food available in this new habitat had virtually no risk of containing lead, the condors experienced a new problem – egg thinning as a result of DDT. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT, was an insecticide popular in the 1940s that was later banned due to the harmful physical effects it has on humans, and other harmful effects it has on the natural world. Due to the condors level on the food chain, they experience a high intake of DDT concentration when they eat carrion. This is called biomagnification. Biomagnification is when toxins travel up the food chain, and reach a higher concentration and are more harmful to those at the top. Because of this magnification, condors are extremely affected by DDT. When DDT was in high use, the Los Angeles coast was a dumping ground for the barrels containing the compound. The barrels are still there to this day contaminating entire food chains. Using assays, Mr. Tubbs collaborates with researchers to determine if the contaminants will affect the condor reproductive system.

Mr. Tubbs’ key to finding his career path was to always keep an open mind. He explained that when he was in high school, he didn’t even know that someone could work at a zoo while doing research. As a student goes through high school or college, they will be introduced to many new paths, and it is essential to keep your mind open and be willing to try new things. He also said that it is extremely important to get as much experience as possible. He highly recommends volunteering when the opportunity presents itself, finding your way into a lab whenever possible, or actively looking for places where you can begin to make a name for yourself. The last piece of advice that Mr. Tubbs gave is to pursue your dreams. He emphasized the importance of staying focused and working hard, which will pay off in the end. All of these things put together are what make you a more well-rounded candidate when pursuing a career path.

Without the work of reproductive scientists, populations of species considered endangered would be substantially lower or even extinct. However, these scientists work together to help save endangered populations of species like rhinos and condors. Their diligent research on environmental factors and hormones affecting reproduction has been very crucial to the conservation of wildlife, increasing their populations all over the world.

Week Five

Fall Session 2020